Hinterland: Singapore and Urbanisms Beyond the Border

| Lead | Milica Topalović |

| Research and Visualisation | Sand: Hans Hortig Food: Marcel Jaeggi Oil: Lino Moser Labour: Ahmed Belkhodja, Saskja Odermatt Water: Architecture of Territory and Benjamin Leclair-Paquet Cross-Border Metropolitan Region Singapore-Johor-Riau: Karoline Kostka Hinterland Typology Drawings: Ani Virhervaara, Bek Tai Keng |

Throughout history, cities have functioned as centres of political and economic power, from which the agricultural and resource-rich hinterlands were controlled. From the nineteenth century onward, new technologies, transportation modes and the opening of trade have introduced a remarkable complexity to the relationship between cities and territories. Today, it is often thought that cities rely decreasingly on surrounding territories for supply and subsistence. Instead, they seem emancipated from the constraints of geography, operating in a global web of dependencies. By contrast, this research is based on a hypothesis that an understanding of the city-territory relationship, the ability to conceptualize it in qualitative terms, and to influence it by means of planning and design strategies, is central in addressing urban sustainability.

At first glance, the island city-state of Singapore is the “city without a hinterland”. Certainly, it is the city whose production grounds and vital resources lie beyond national borders. The economic incorporation of hinterland territories in Malaysia, Indonesia, Southern Asia and beyond, have remained both a necessity and a profitable opportunity for Singapore.

The research concerns the problematic of Singapore’s hinterland at various territorial scales, from local to global. The five key resources for Singapore—sand, water, food, oil, and human labour—as well as territorial dynamics of resource extraction, flows and accumulation at different scales—were put in focus. The investigation has revealed processes and procedures with which each of the resources is increasingly sought by the citystate in a geopolitical frame, in the countries of the Asean and beyond. This increasing dependency on cross-border territories, ever further removed, is the source of vulnerability for Singapore. At the same time, these specific restrictions give highly distinctive profile to Singapore’s development practices, its urban character and form. Each of the five resource hinterlands has been described through maps, plans, diagrams, and text, from the perspective of urban history, and in terms of socio-political, economic, and environmental development characteristics and policy choices pursued.

The research does not represent the accustomed view of Singapore as an island developed on the paradigm of a global city-state, but as a city whose present and future are tightly connected to its cross border metropolitan region and the rest of South Asia.

Eclipse

The perception of all remote territories, from nature’s wilderness to rural countrysides, has always been created from an urban perspective: the periphery has always been imagined from the viewpoint of the centre. The observation of a city’s hinterland can only begin when the city itself is eclipsed: only when the centre of gravity and its blinding sources of light become temporarily obscured can the phenomena unfolding in its shadow be adequately perceived and analysed. The resulting view of the city from the “outside,” reveals new perspectives and potentials.

Hinterland is a broad category used to signify the economic incorporation of territory to a given (urban) centre. Throughout history, cities have functioned as centres of political and economic power from which the agricultural and resource-rich hinterlands have been controlled. From the nineteenth century onward, new technologies, transportation modes and the opening of new trade routes and spaces have widened distances and introduced remarkable complexities between cities and their hinterlands. Today, the significance of city-hinterland linkages is often brought to question where it is often assumed that contemporary cities rely decreasingly on their immediate surroundings for supplies and subsistence. Instead, the cities are frequently seen as being emancipated from the constraints of geography, operating in a global web of dependencies, flows and exchanges.

By contrast, this research is based on the hypothesis that understanding city-hinterland relationships—the ability to conceptualize it in qualitative terms, and to influence it by means of planning and design strategies—is central to urban sustainability.

Singapore represents an ideal case to examine the contemporary city’s relation to its hinterland. At first glance, the island city-state of Singapore appears as a paradox, and a highly successful one. Singapore is the self-declared “city without a hinterland,” whose production grounds and vital resources lie beyond national borders—and yet, Singapore’s urban and economic growth does not seem to be threatened. The economic incorporation of hinterland territories both near and far, remain a necessity and an opportunity for Singapore.

The research reveals the dynamics of hinterland urbanisation at various scales, from urban to planetary. It addresses the critical socio-political problematic of city-hinterland relationships, and suggests that new forms of multiscalar thinking, planning and governance have become necessary.

The research does not represent the accustomed view of Singapore as an island developed on the paradigm of a global city-state, but as a city whose present and future are tightly connected to its cross border metropolitan region and the rest of South Asia.

Hinterland

Metabolism

Extraction

Infrastructure

Organisation

Accumulation

Hinterland

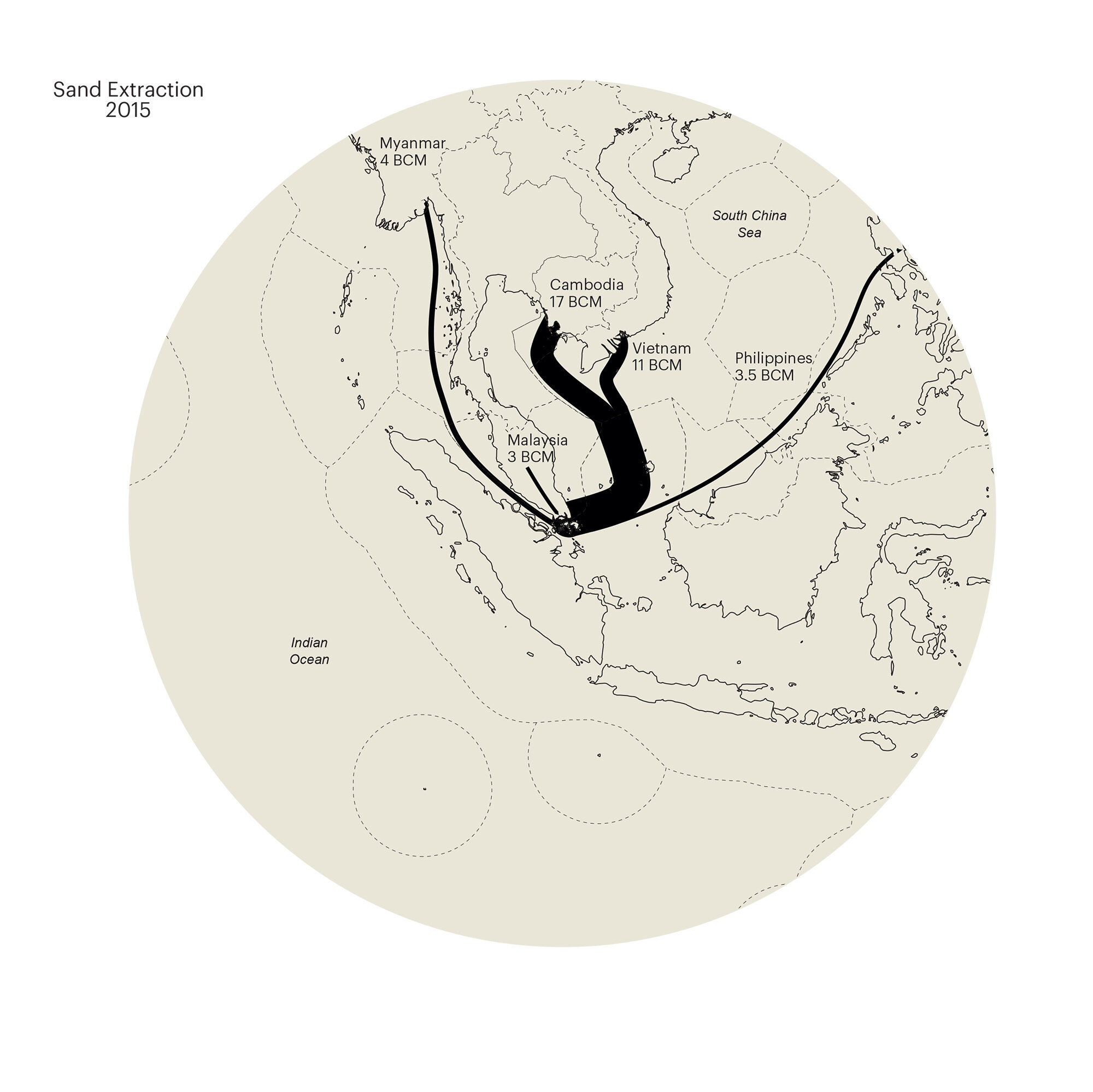

The lack of locally available sand together with sand-export bans in neighbouring countries force Singapore to constantly expand its sand hinterland. Today, sand continues to be imported from countries throughout Southeast Asia, while extraction sites keep shifting further afar to include sources as removed as China and Myanmar.

Metabolism

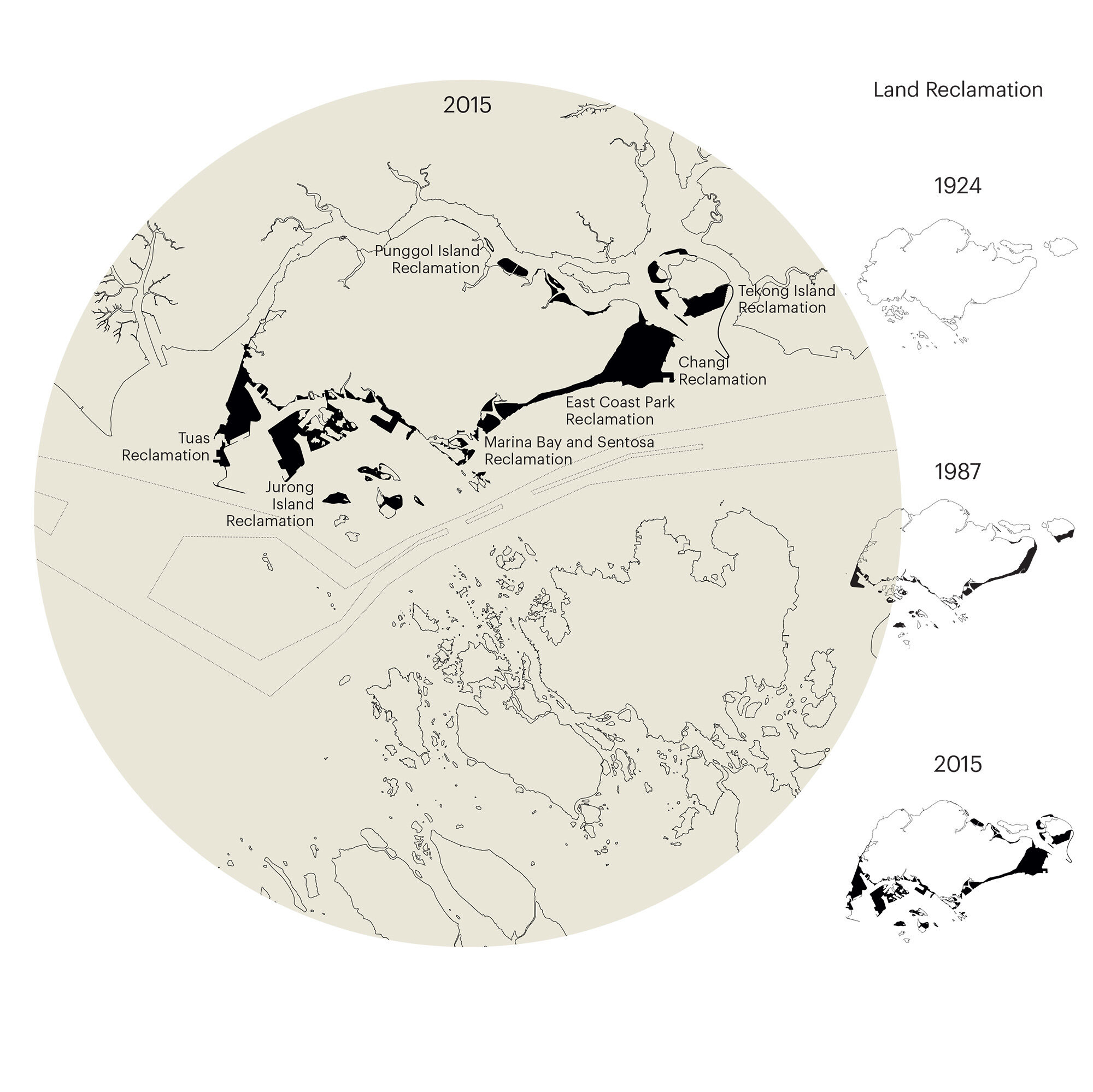

Singapore is built on, and of, sand but local sources are scarce. In order to fuel the island’s physical expansion, foreign sand has to be continuously imported. Land reclamation absorbs vast quantities of coarse sea sand—an infill material—while fine-grained river sand is utilized by the construction sector in the production of concrete. Singapore’s ability to metabolize sand has completely reshaped the island’s landscape, and quite literarily supported “nation building” by allowing a majority of its population to reside in high-rise new towns.

Extraction

The growing radius of Singapore’s sand hinterland culminated in what has been termed Asia’s “sand wars.” Countries in the region have accused Singapore of consuming their territory, suggesting not only the loss of an important resource, but also a threat to their territorial sovereignty and the stability of national borders. As a result, sand bans ensued throughout the region, forcing Singapore to seek new sources.

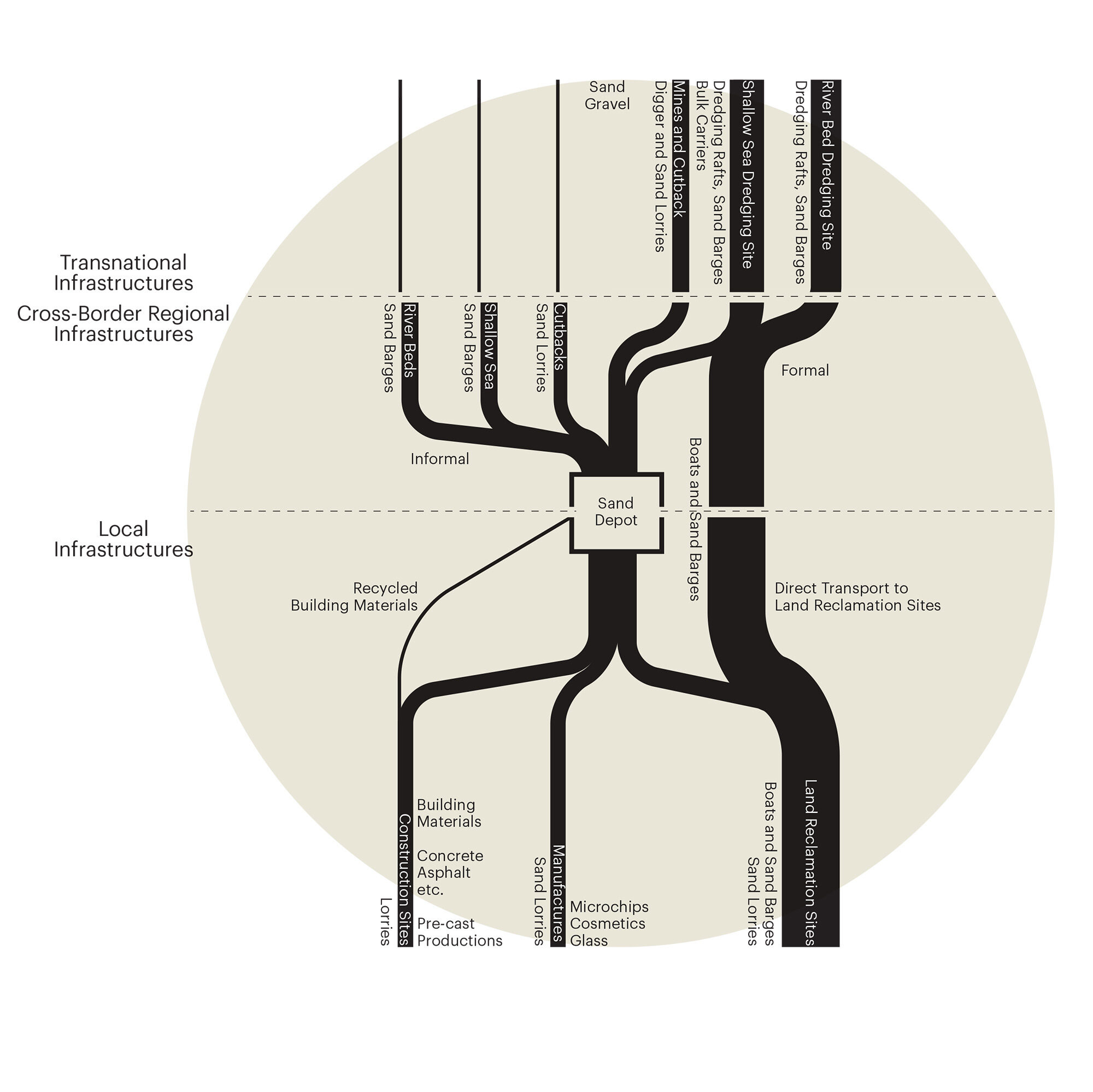

Infrastructure

Sand trade is characterized by an absence of rigid infrastructures. As most sand is obtained through dredging and arrives by boat, the entire process of extraction and transport is waterborne, to include sand barges, bulk carriers and dredging rafts as crucial vehicles of the trade. The raw material is susceptible to change hands during its transfer to Singapore, where documentations pertaining to its country of origin are sometimes falsified to circumvent national provisions and laws prohibiting exportation. Sand arriving to Singapore is often anonymous as its trade history is removed and its region of origin becomes uncertain.

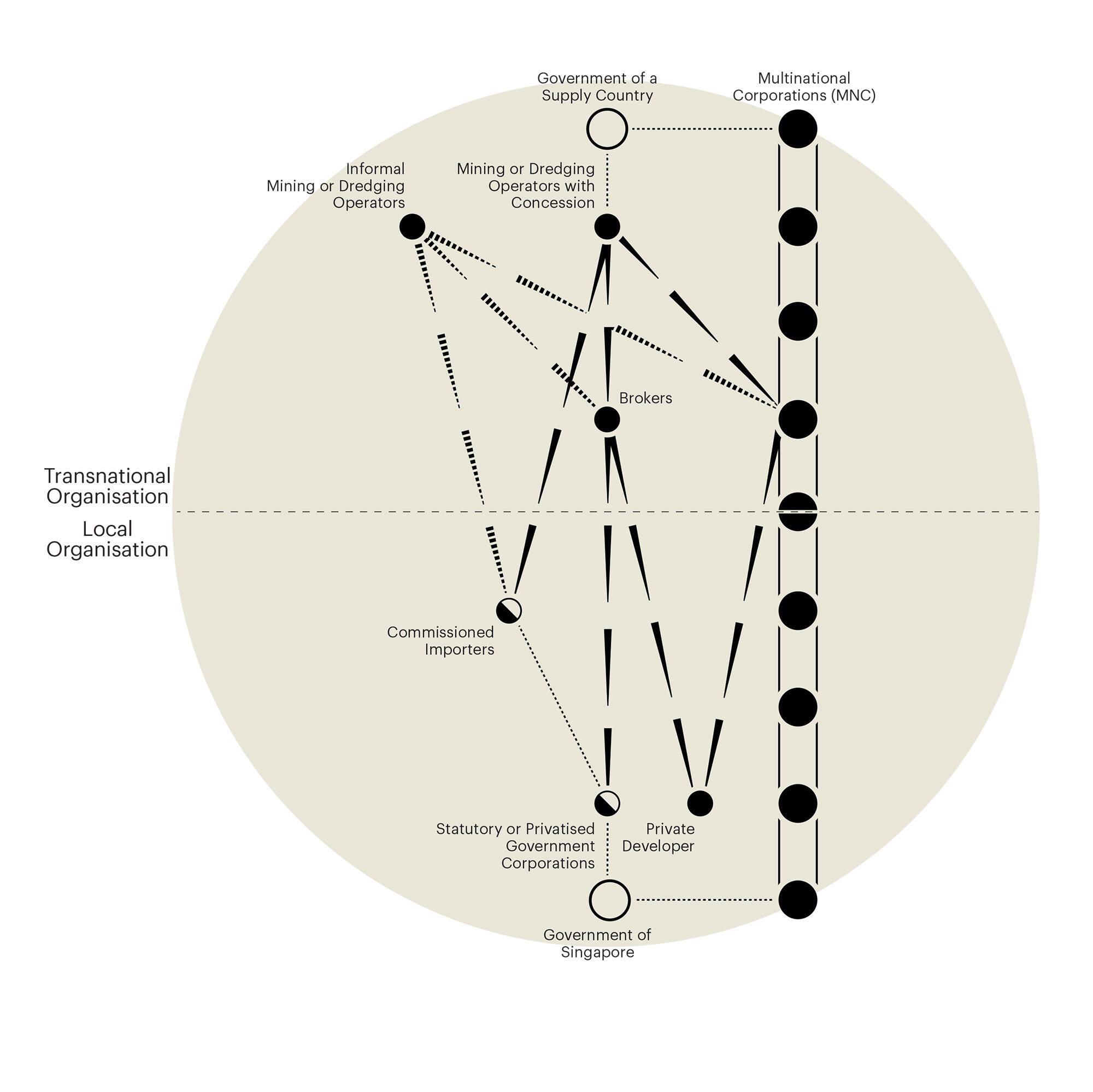

Organisation

Singapore’s government explicitly states that it is not actively involved in any form of sand importation and that government agencies only buy from authorized private contractors. For this reason, the government cannot trace back the full material flow, trade contracts, or the circumstances and consequences of extraction and trade. Sand import is negotiated among middlemen and sand brokers, who operate in a vague, underregulated stratum between sub-state and supranational levels. The ambiguous organisation allows room for informal activities to become an integral part of the import process.

Accumulation

Although Singapore has a small land area, land has never been perceived as a limited resource here, but rather as a vast potential to be released. Major Singaporean industries are located on artificial land, as well as the defence complex and other strategic infrastructures. Through the process of land reclamation, the economic and strategic engines of the county are continuously recreated. Today, the celebrated “Singapore model” represents a paradigm of urban development inextricably tied to the continuous transformation and reclamation of land.

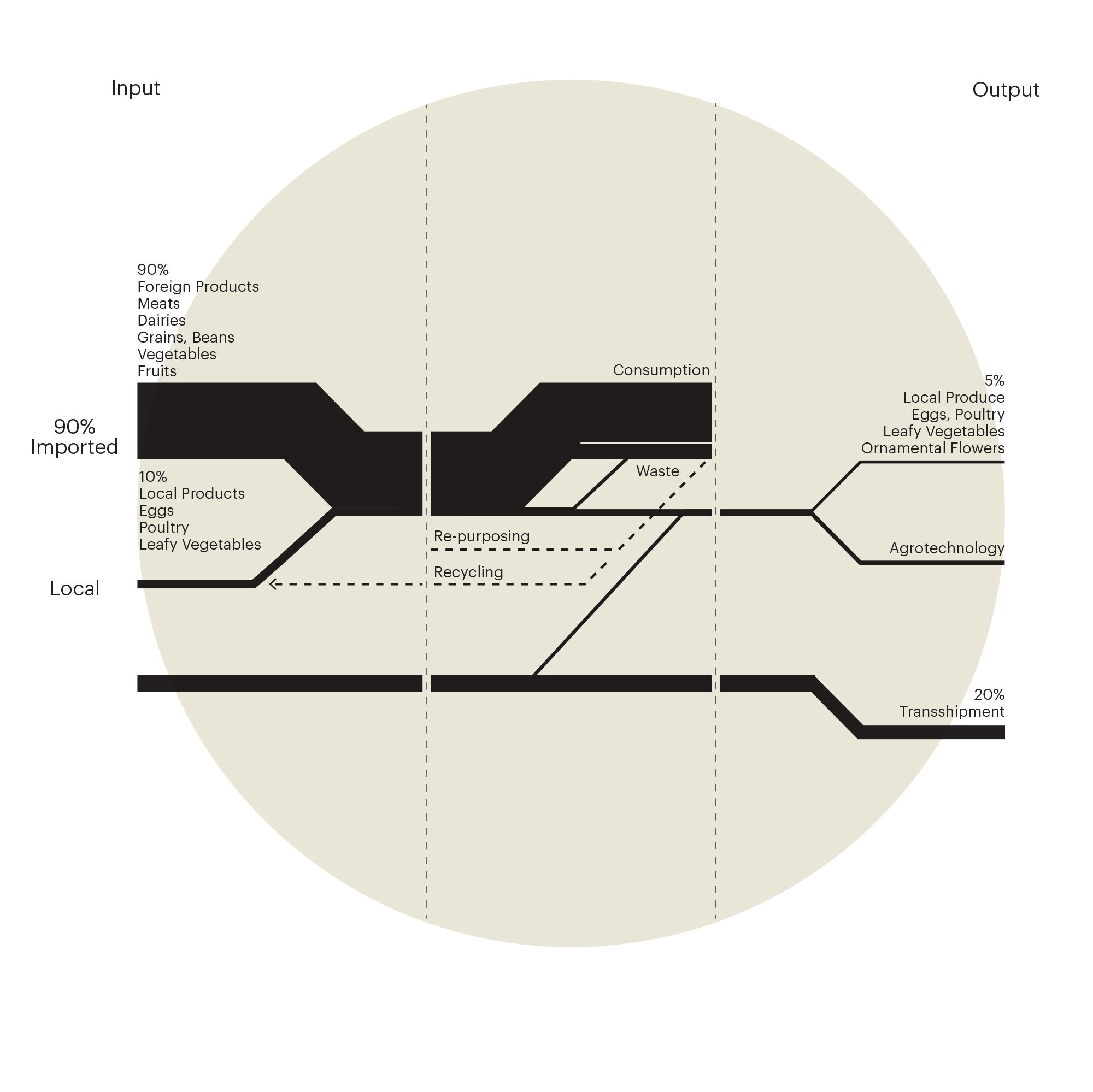

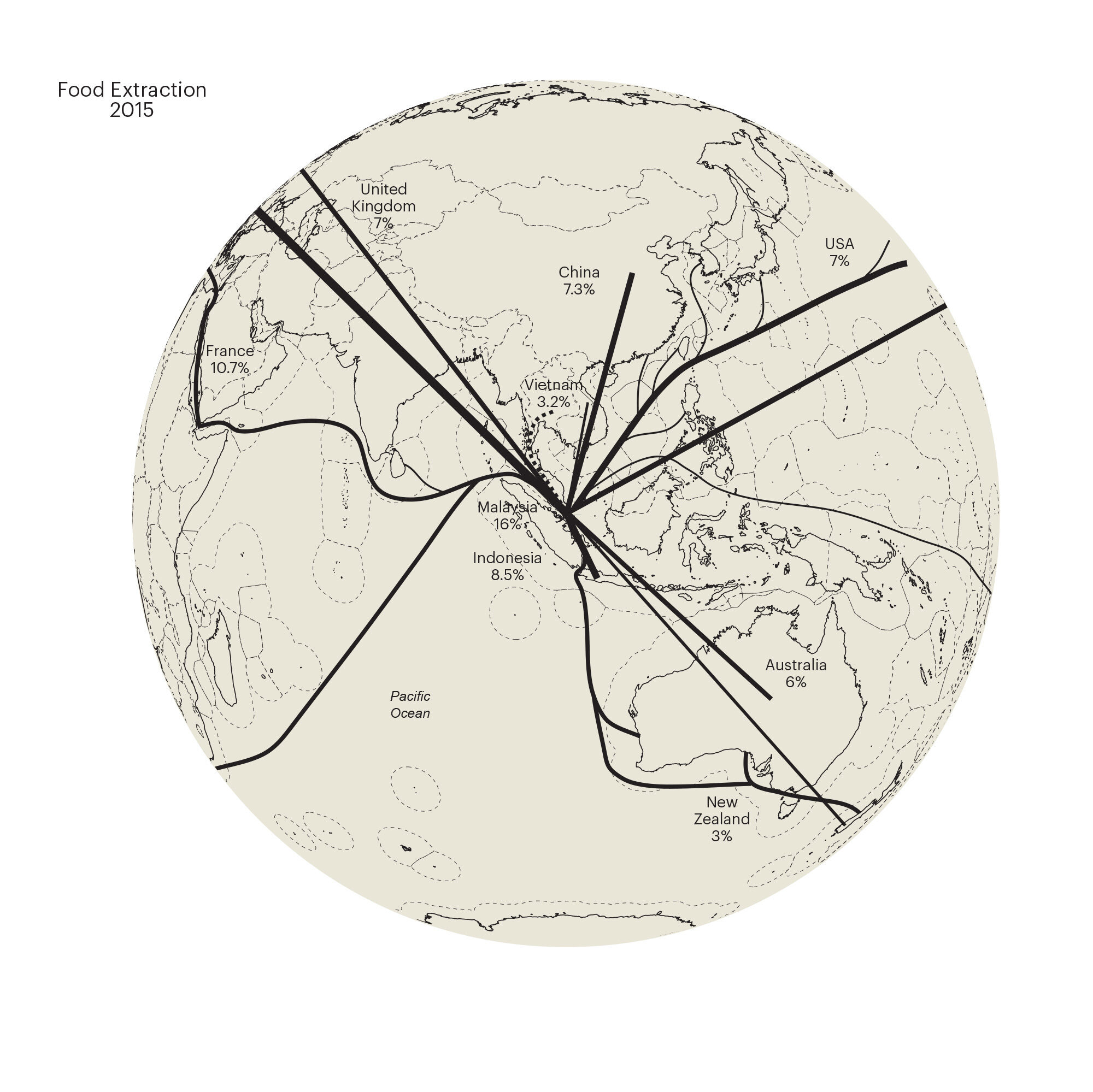

From Singapore’s multi-ethnic culture has emerged a multitude of cuisines rooted in local as well as far-away culinary traditions. Due to its limited food production capacity, the city-state is fully reliant on foreign exports and is among Asia’s largest importers. Today 90% of all food consumed in Singapore is imported; and 90% of it arrives by sea. Paradoxically, Singapore is considered to have relatively high food security, despite its insubstantial food production capacity and reliance on volatile external supplies.

Hinterland

Metabolism

Extraction

Organisation

Accumulation

Hinterland

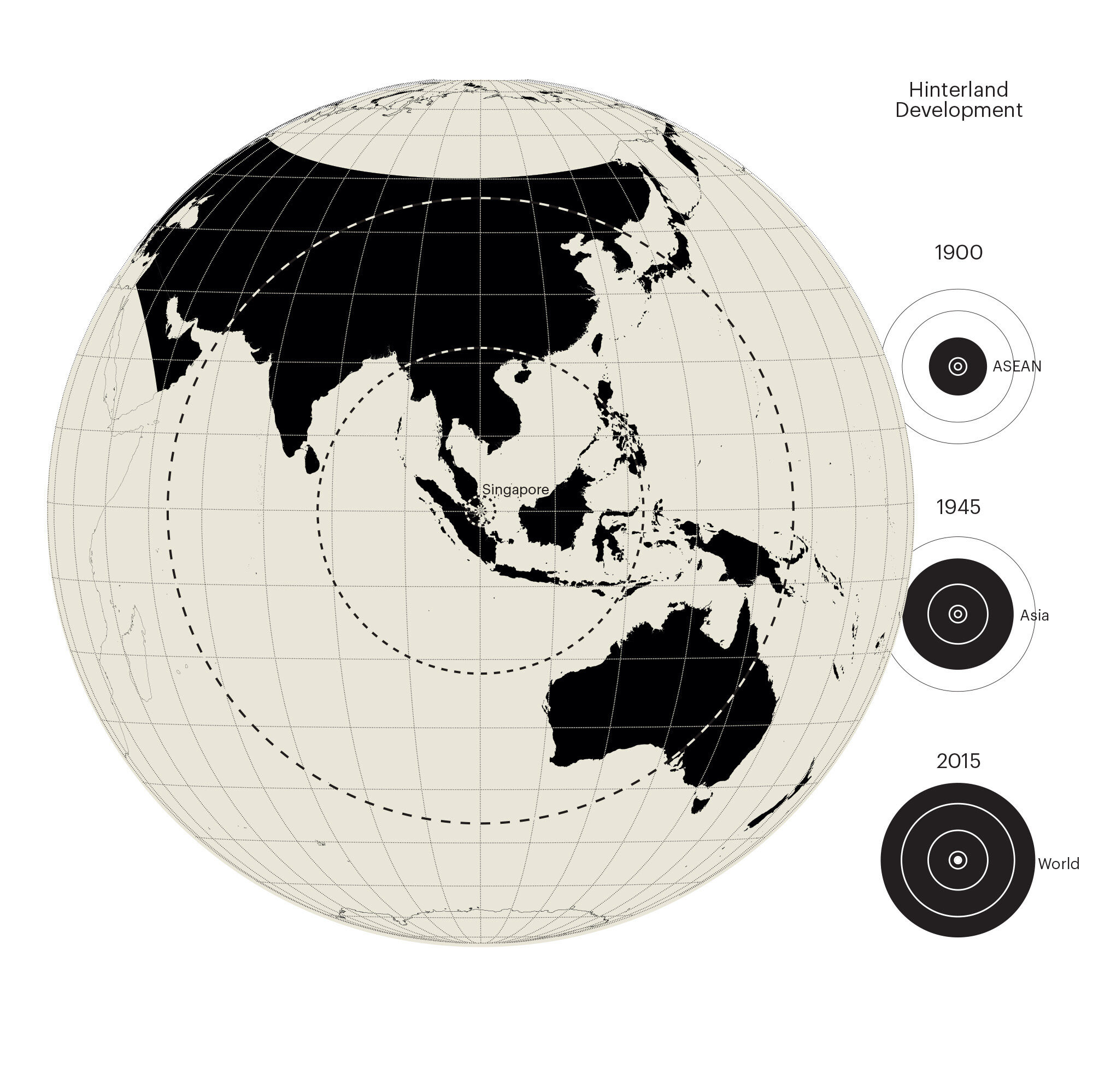

Singapore’s respective food hinterlands are defined by their spatial extensions and specific roles within the city’s food supply system. Over time, these hinterlands have continually expanded to further removed territories as food preservation and long-distance transportation technologies have evolved, and as wealth in the city-state generated new consumer demands. Free trade regulations and agreements for food products fostered the role of Singapore as a distribution hub for Southeast Asia, while traditionally linking its adjunct productive territories in the regional hinterland to a global food chain.

Metabolism

The island’s food imports are diverse, largely because its domestic production is minimal, and also because re-exporters trade in a wide range of products targeting markets across Asia. In 2011 for example, Singapore’s imports of agricultural products and processed foods (US$12.1 billion), ranked it the country with the highest food per capita consumption in Southeast Asia. This exposure to imported foods leads to unstable domestic prices, but perhaps more worryingly, to modernized diets and greater health issues.

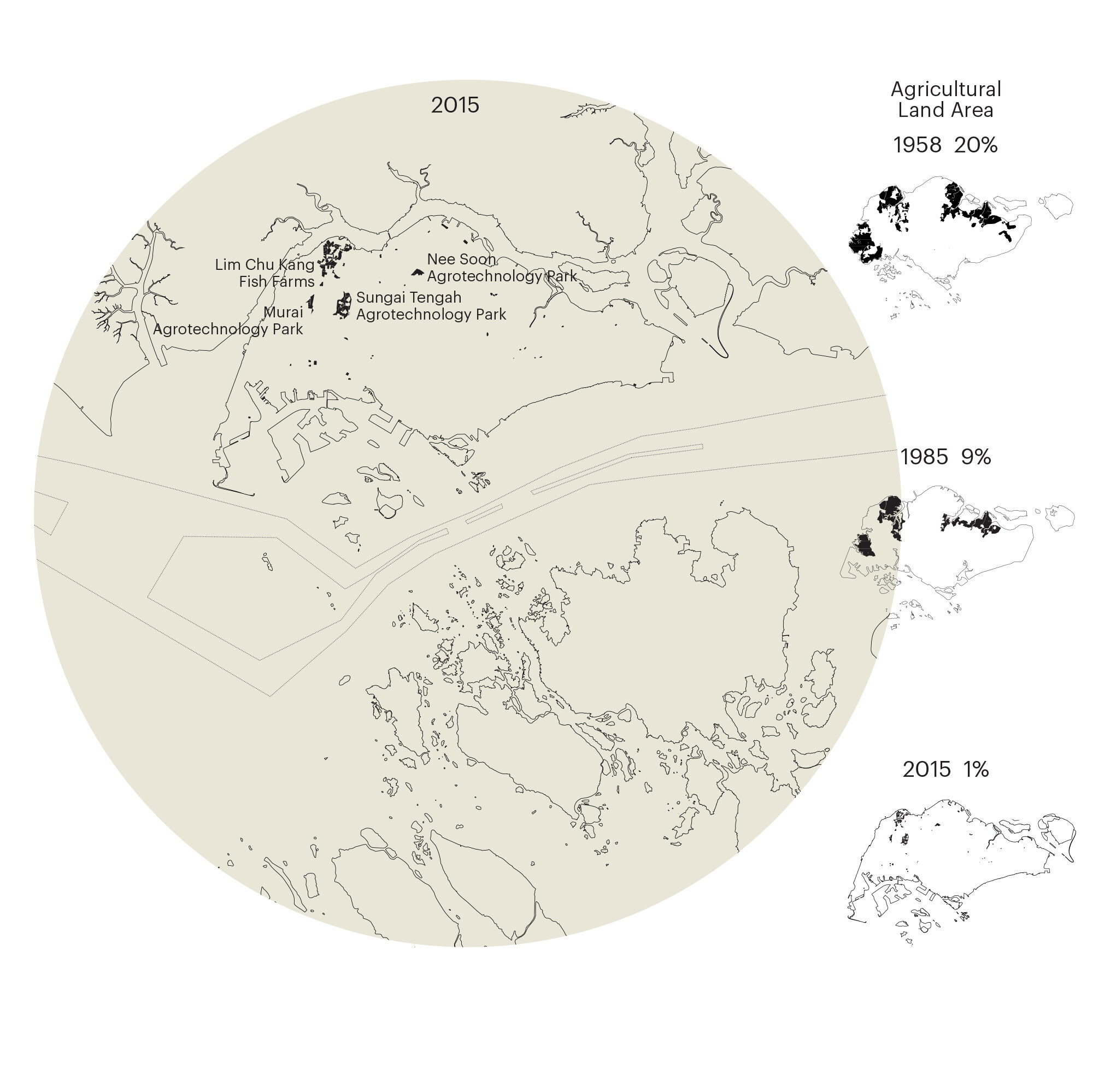

Extraction

Today, most of the fresh food arrives from neighbouring countries, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, either by ship or truck. At the same time, the growing sophistication of cold-chain infrastructures coupled with advanced food processing technologies have expanded Singapore’s food hinterlands to a global scale. To improve the resilience of its food supply and diversify its sources, Singapore actively promotes the creation of extra-territorial food producing zones in rural China, Southeast Asia, and beyond.

Infrastructure

Food imports to Singapore are subject to stringent quality controls, whether they be live pigs arriving by barges from Riau Archipelago, or boxed perishable cargo flown from afar. Formal quality-control measures are imposed alongside single-products “farm-to-fork” chains within and beyond Singapore’s borders. The island’s sophisticated storage infrastructures and its fast-paced, nocturnal distribution rhythms present an invisible backstage for food products before reaching the consumers in supermarkets, restaurants or subsidized food courts.

Organisation

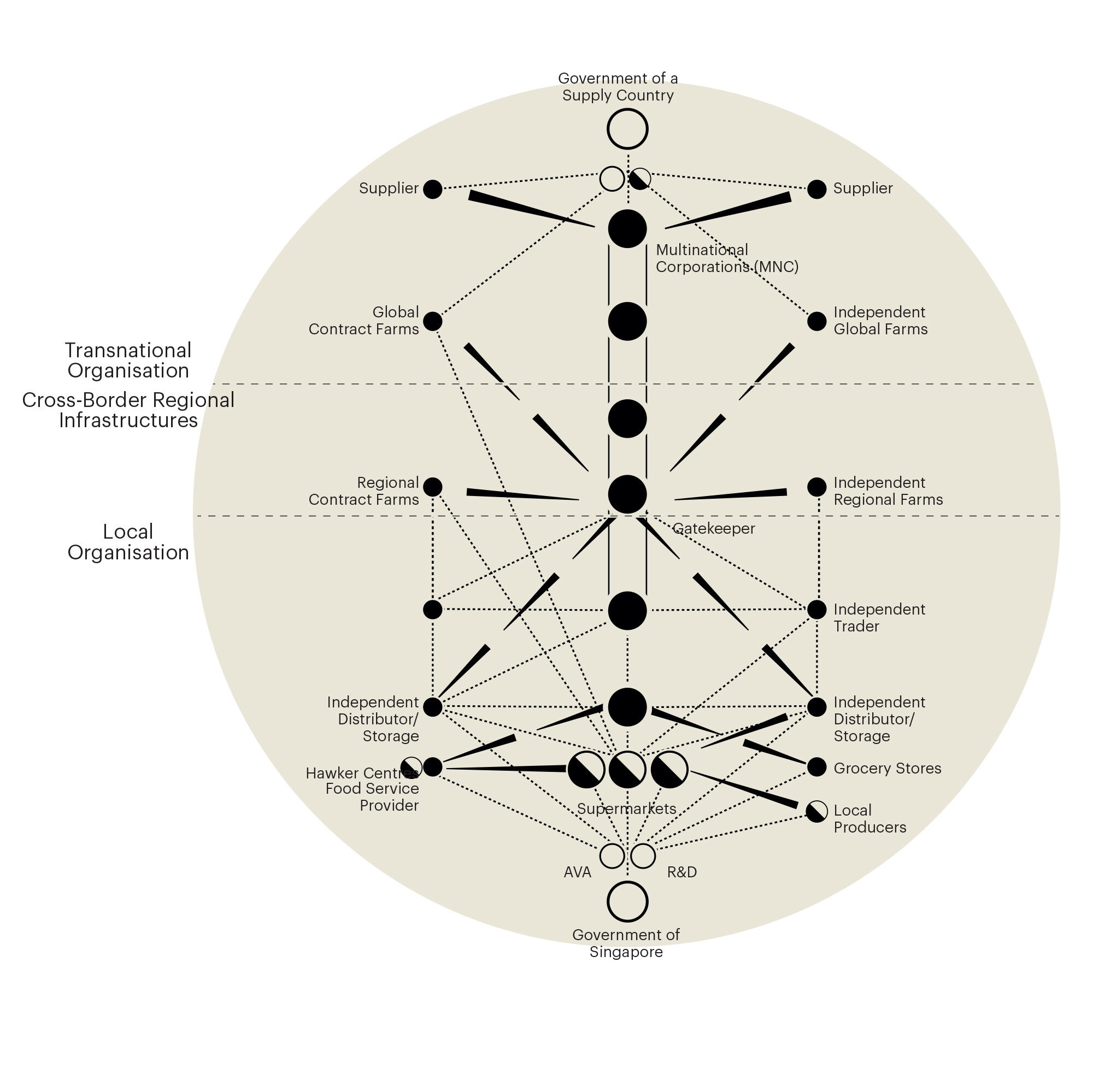

Singapore’s public policies enabled multinational companies and supermarket chains to take on a dominant role in its food supply. As a consequence, Singapore is increasingly dependent on globalized food systems, leaving little room for traditional providers such as regional fishermen and contract-farms in Malaysia to operate. By contrast, the city-state’s strong push to create an internal Research & Development environment will allow it to further develop and export agricultural technologies.

Accumulation

Singapore’s agriculture sector experienced extreme transformations characterized by a forceful structural and spatial regrouping. After phasing out traditional farming through a government mandate in the 1980s, today’s agricultural production has become limited to state-sponsored agrotechnology parks. This high-tech urban agriculture has made Singapore one of the world’s most efficient producers. Strict agricultural landuse policies are closely linked with the productivity and profitability of existing farms and their innovation capacities towards overcoming natural resource constraints.

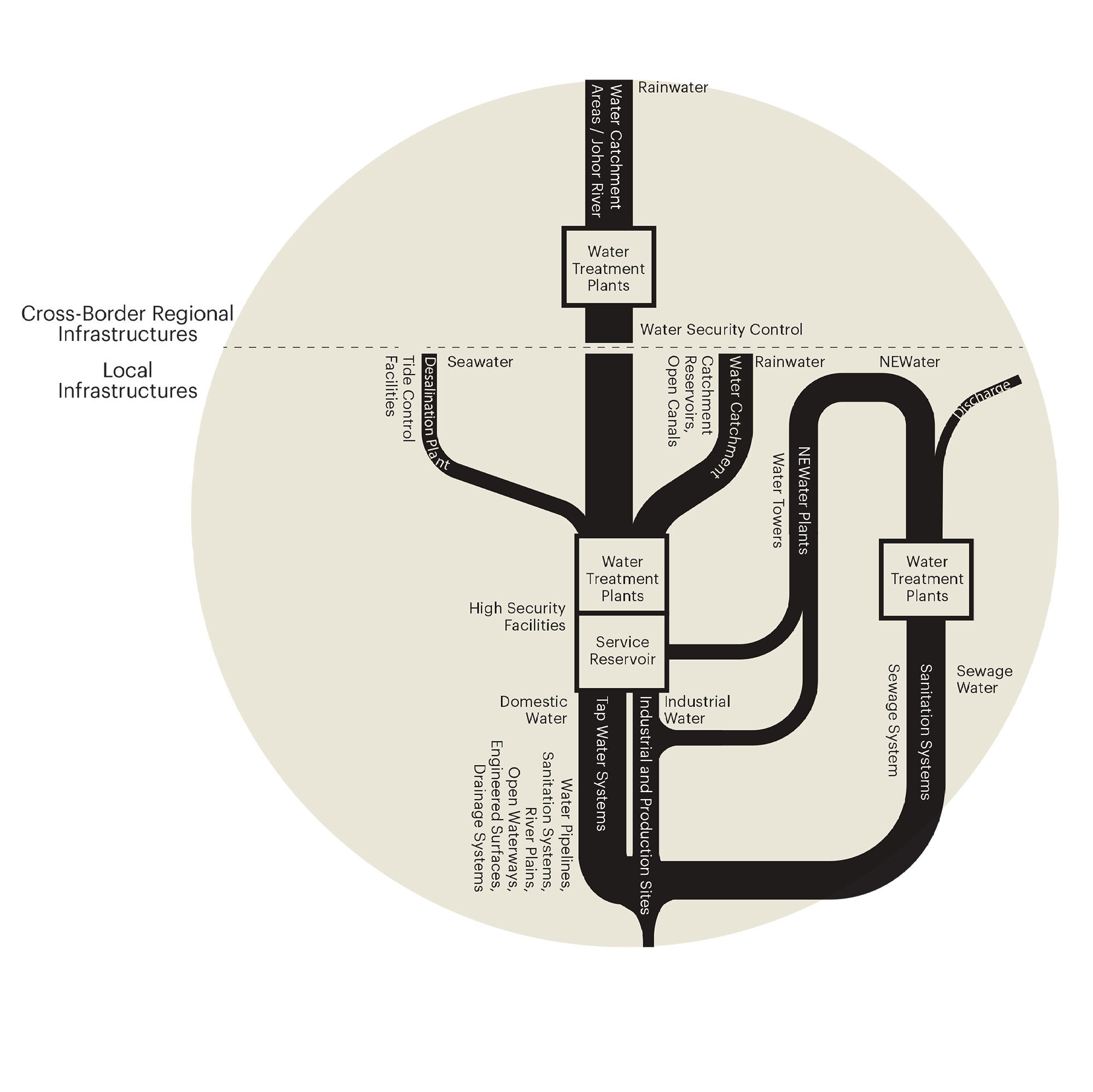

Although water is omnipresent in tropical Singapore, where precipitations are higher than the world’s average, the island has no natural water sources and rainwater catchments to support its population and industries. In order to meet local demands for water, Singapore has had to rely on complex calculations and negotiations involving water geopolitics, technological investigations, land engineering and consumption changes in everyday life.

Hinterland

Metabolism

Extraction

Infrastructure

Organisation

Accumulation

Hinterland

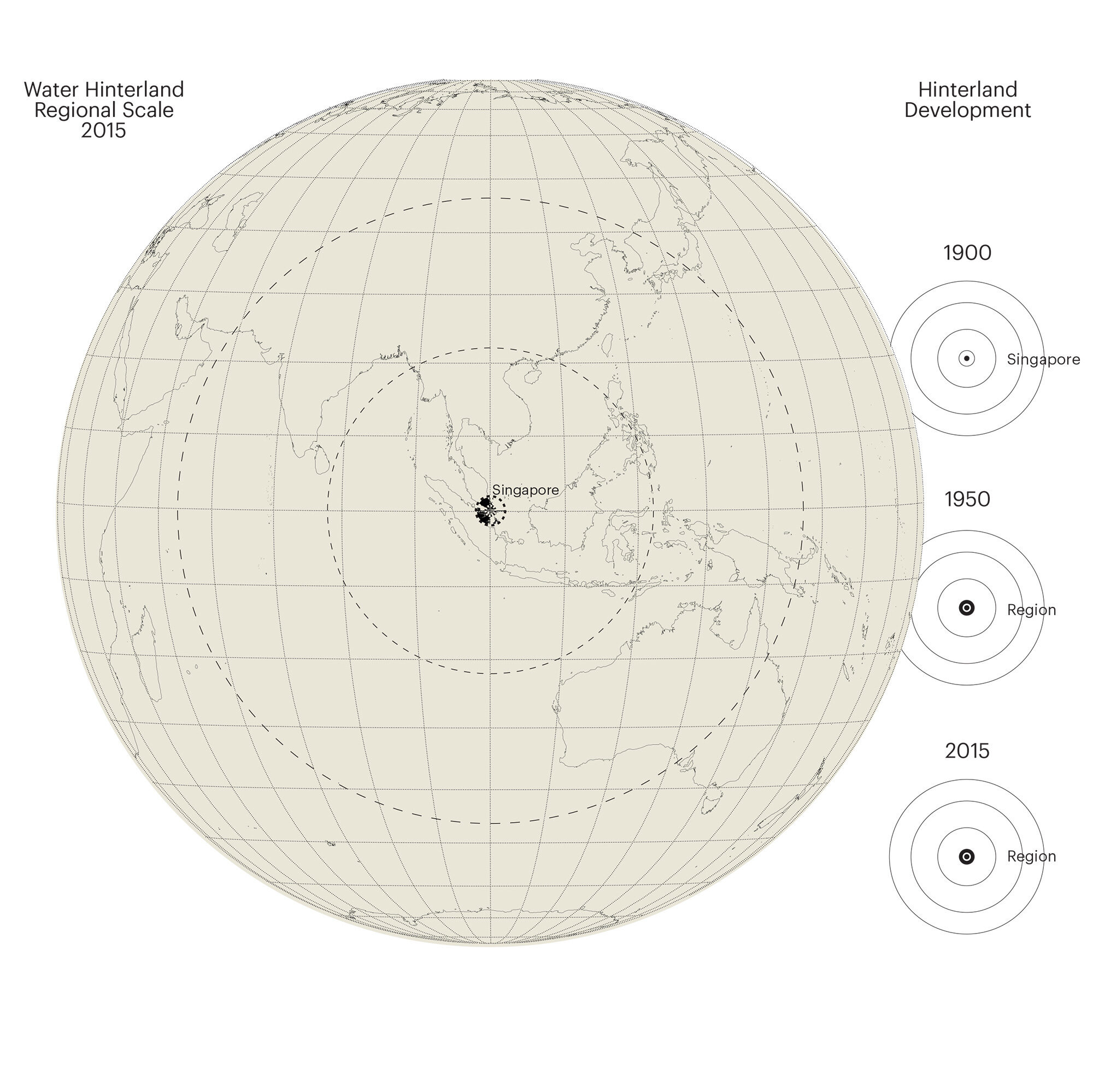

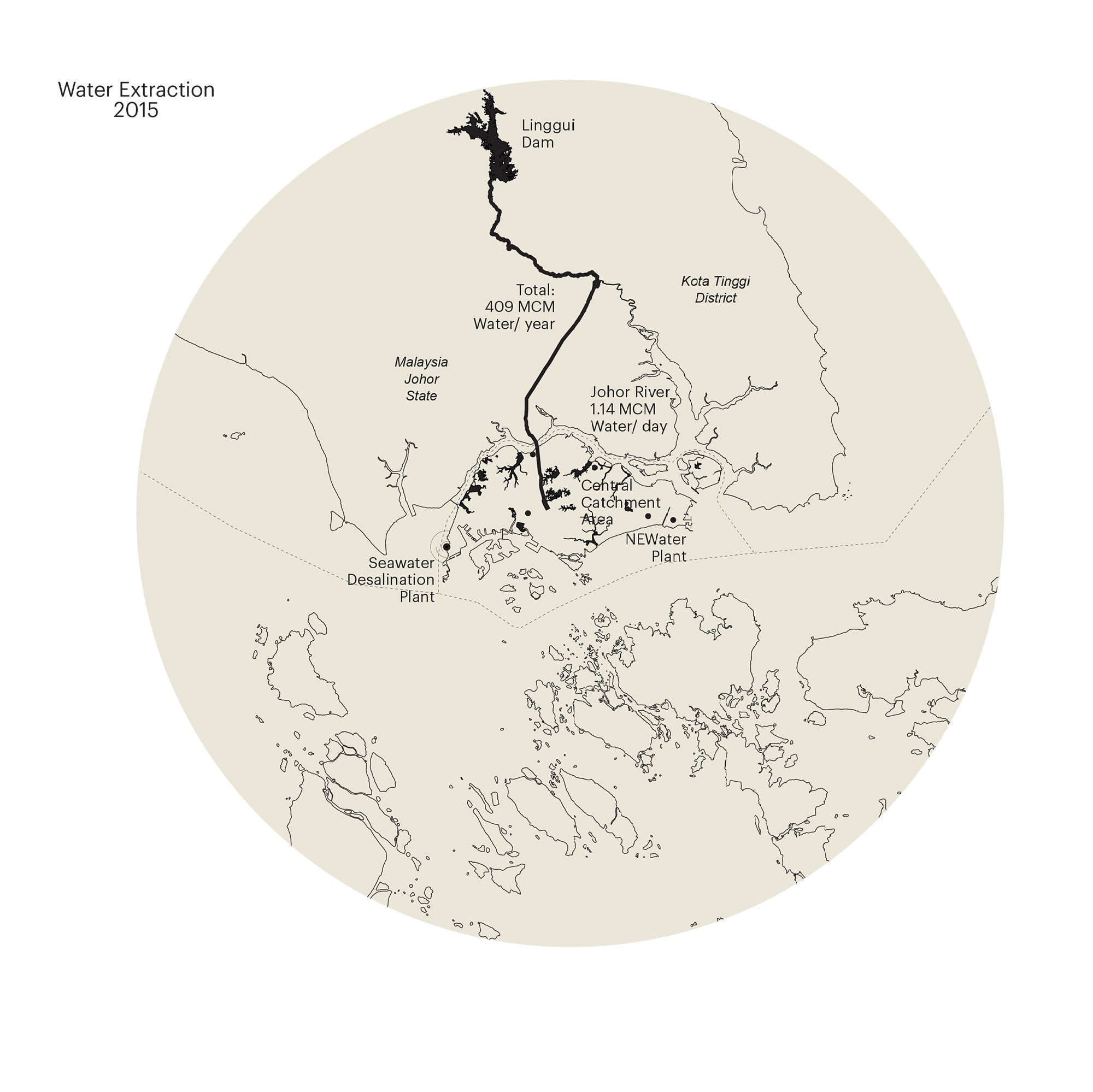

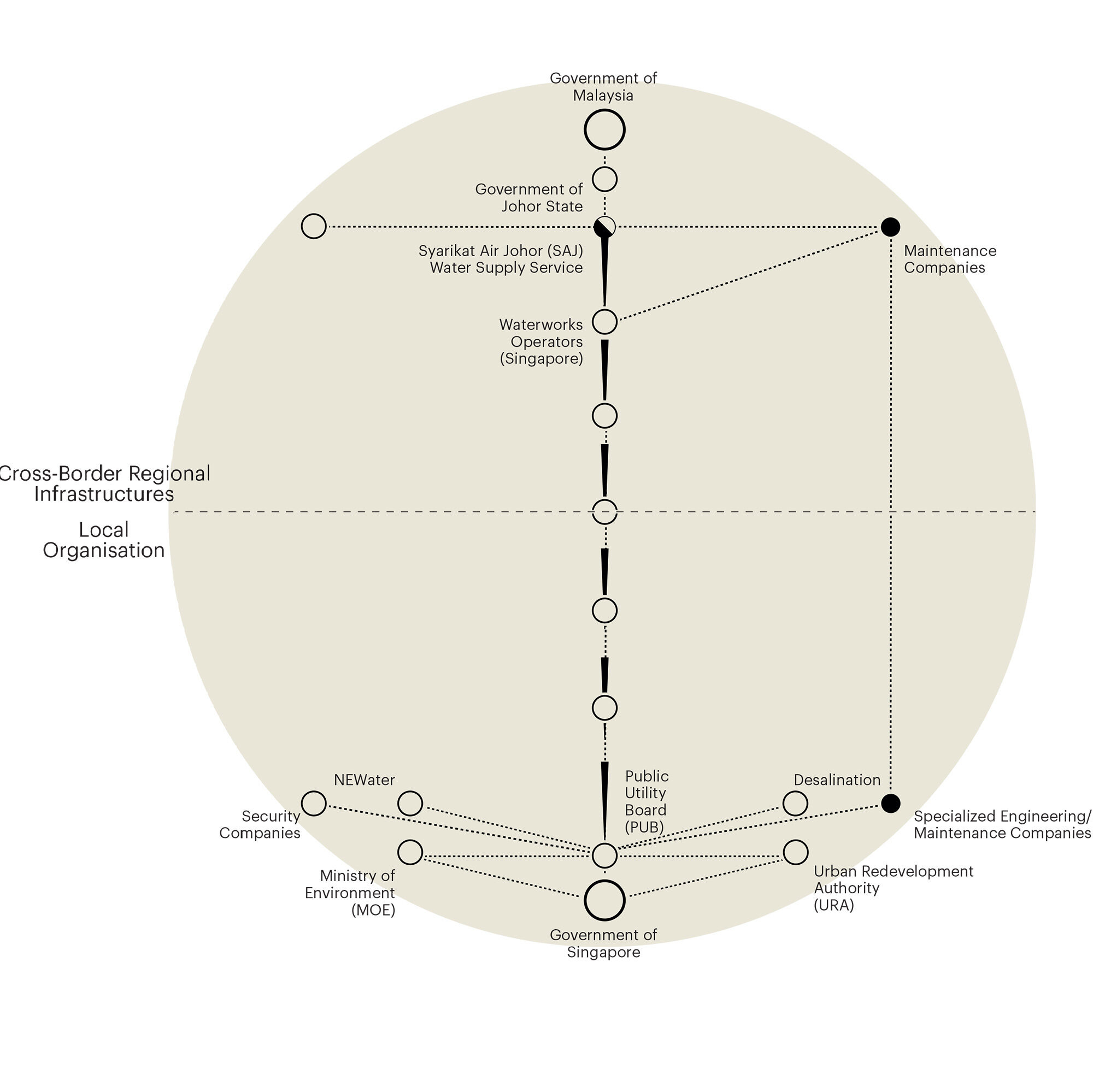

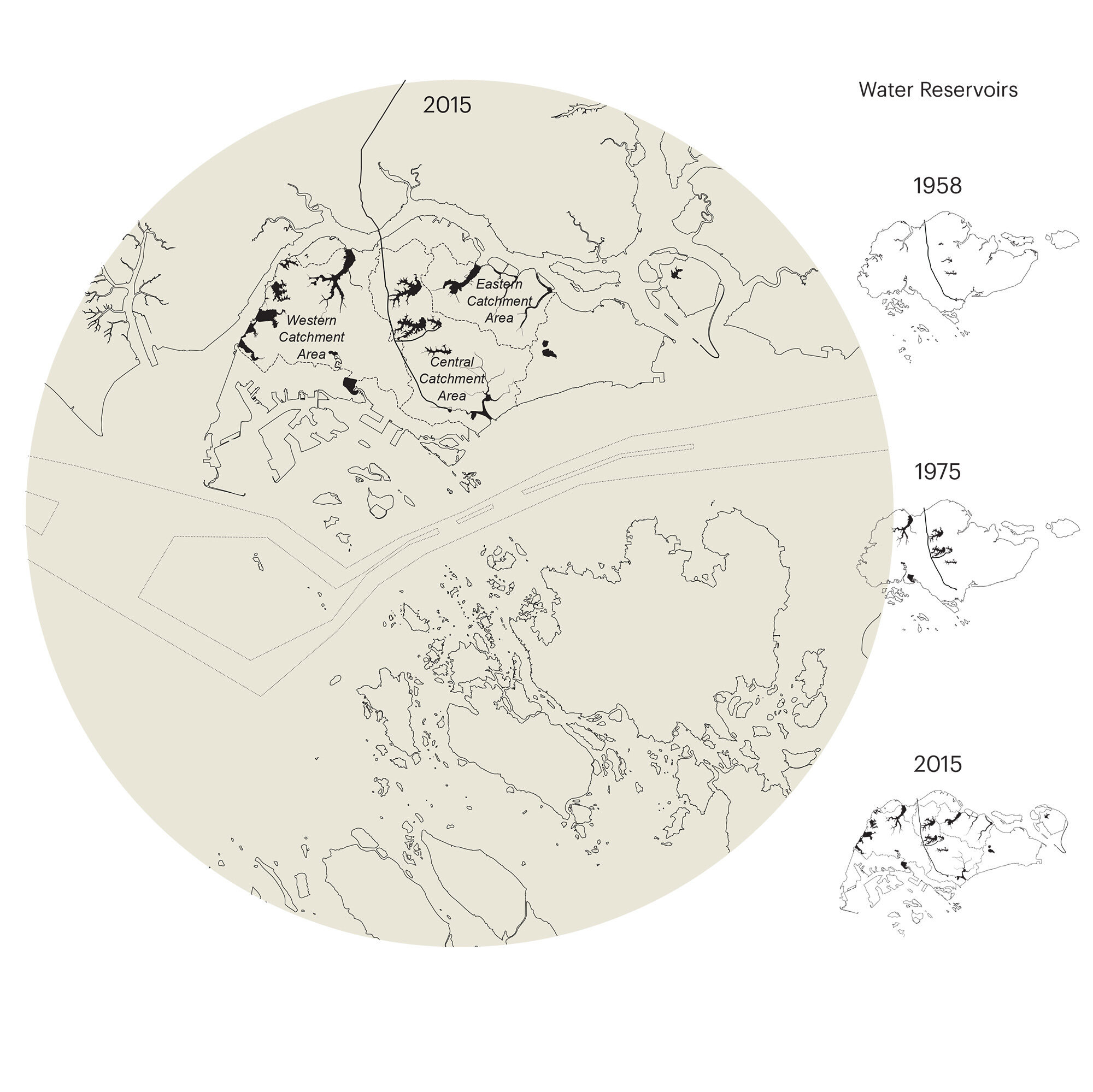

The nature of water infrastructures make long-distance water transportation difficult, while water hinterlands for cities without natural sources are usually small in size. Singapore has been importing water from Malaysia since 1927, when the city-state’s population reached almost one million. Singapore’s regional water hinterland has since diminished, stretching only 70 km north into Johor state today. Moreover, the prospect of continuing water imports from Malaysia has become highly uncertain due to problematic bilateral relationships between the two states, as well as Johor’s rising demand for water, justified by its increasing population.

Metabolism

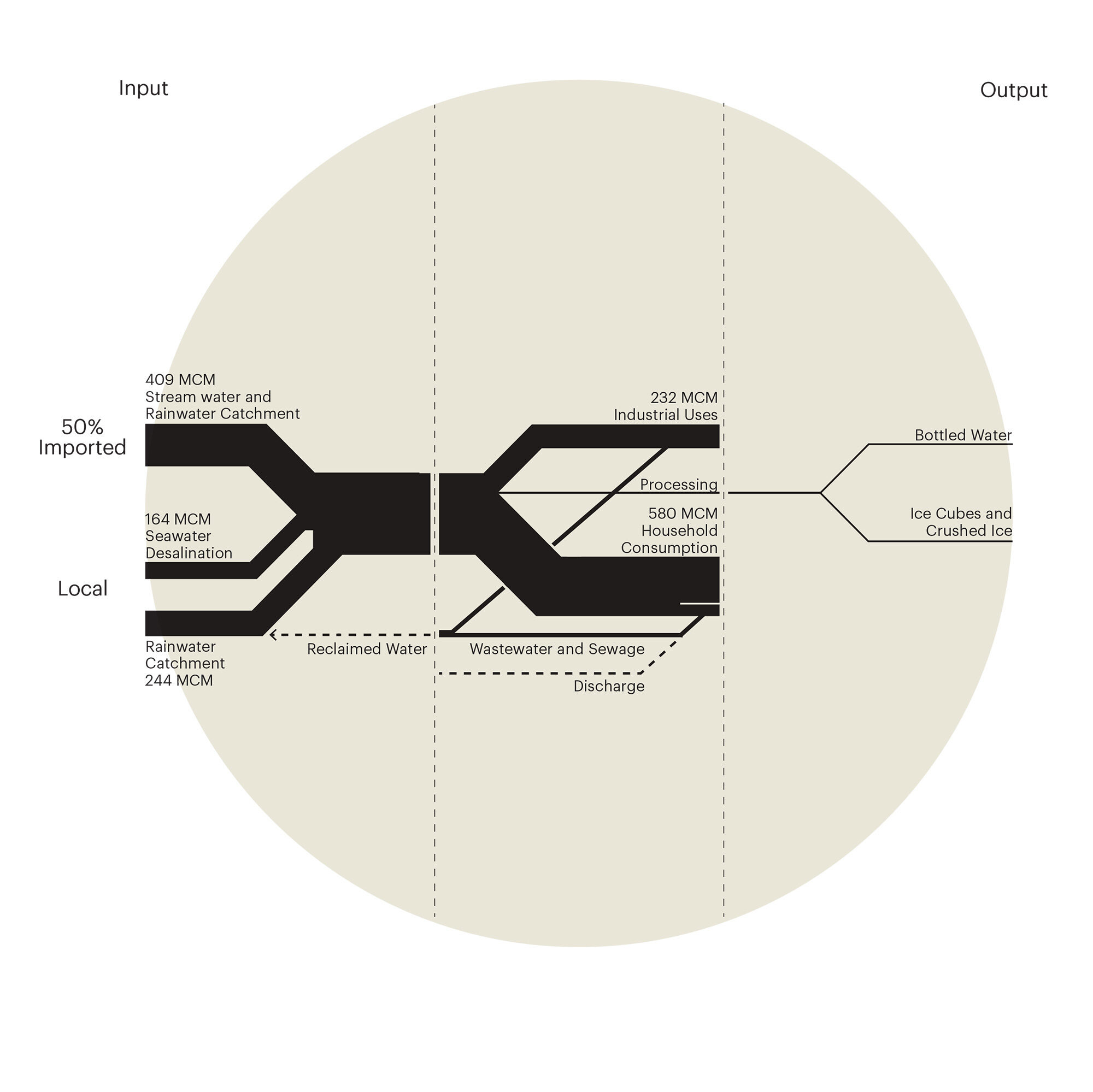

Though every drop of rainwater in Singapore is used and reused, its total demand for water far exceed the natural precipitation catchment. Singapore’s water derives from four different sources, the so-called “4 Taps” of the national water policy. To lower its dependency on Malaysia, from which about 50% of its current supply still comes from, Singapore has invested into intensive research and futuristic infrastructures over the past thirty years. Today, the upside of the city-state’s vulnerability towards this precious resource has become its water know-how, where Singapore has evolved into a world-leading exporter of water technologies.

Extraction

Starting far up in Pandang state, Malaysia, water destined for the Singaporean market is first stocked in a single gigantic reservoir inaccessible to the public, located in the middle of a rain forest. After being released at the Linggui dam, the water is pumped into a high-security treatment plant before being released further into underground pipelines that cut through Johor state and eventually cross the causeway from Malaysia to Singapore. These hybrid installations of water transport and military security are a physical manifestation of Singapore’s relation with its regional water hinterland.

Infrastructure

Singapore’s water flows through different territories and installations which each have their own rules and security levels. Throughout the island, water infrastructures are highly elaborated and formalised and consist of different types of water reservoirs, treatment plants, flood control facilities, pipelines and gutters; the commitment to rainwater catchment gives the city-state’s landscape a highly engineered appearance. Engineered lines further connect Singapore to the peninsular of Malaysia.

Organisation

The organisation of water trade between Malaysia and Singapore is entirely based on a bilateral contract signed between the two countries in 1962 and valid until 2061. All segments of water capture, treatment and store process are controlled directly by governments and their agencies in both countries. The government of Singapore is obliged to pay monthly rents and cover the maintenance costs of Malaysia’s exporting water infrastructures. Water is the most sensitive strategic resource in this region, where private sector did not expand far beyond trading bottled water and ice-cubes.

Accumulation

While Singapore began to develop rainwater catchments when it became a trading port at the turn of the twentieth century, it only started to shape its territory for catchment purposes in the 1970s. Existing reservoirs have been enlarged, while damming rivers connected to the sea created new sources. Today, Singapore’s surface is entirely engineered for water catchment and protection against water pollution through a network of infrastructures. Although parts of the island’s surface still appear to be untouched, even natural parks and seemingly wild terrains have been rebuilt to collect rainwater. The entire accumulation of water is, in fact, artificially controlled.

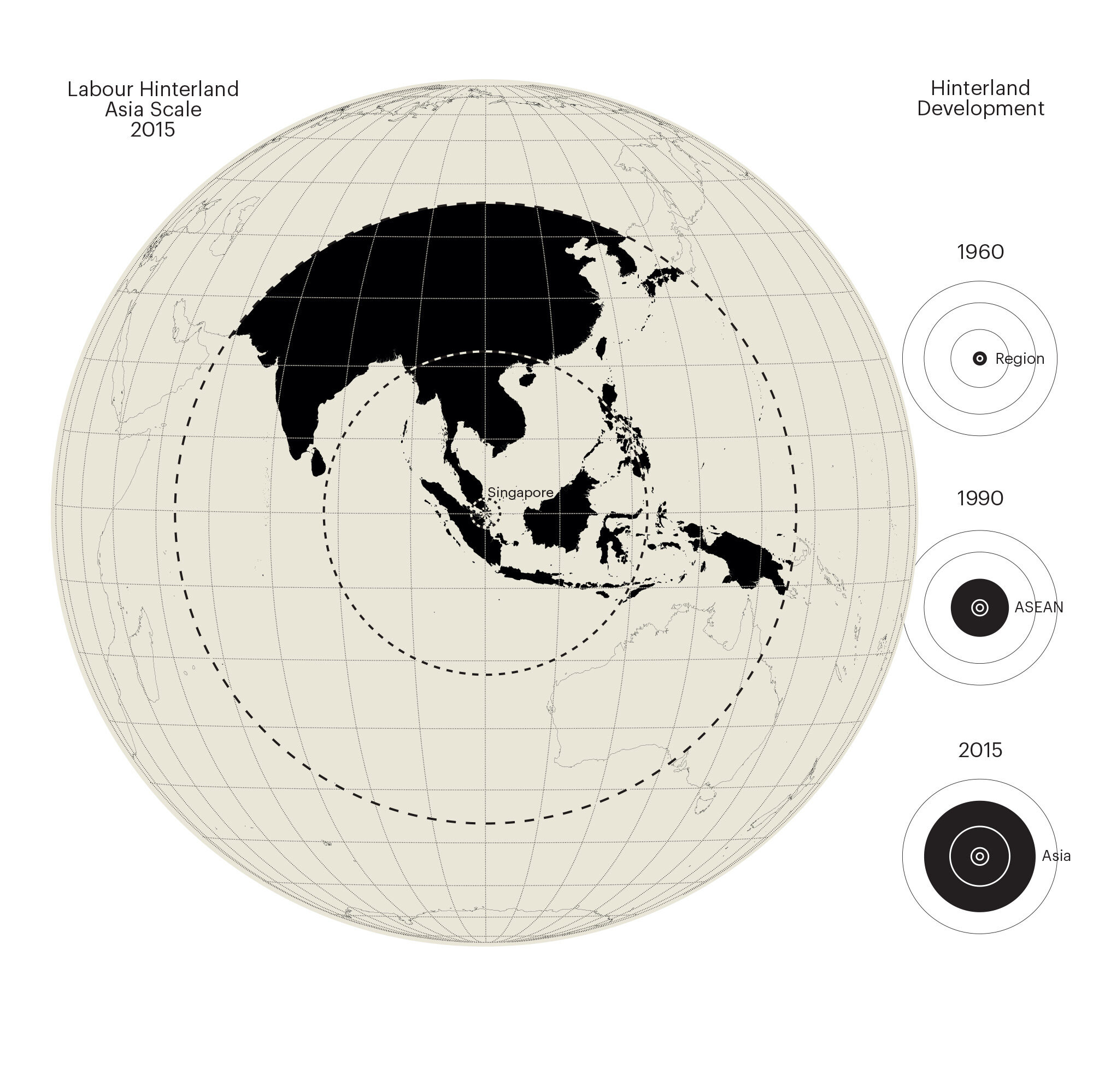

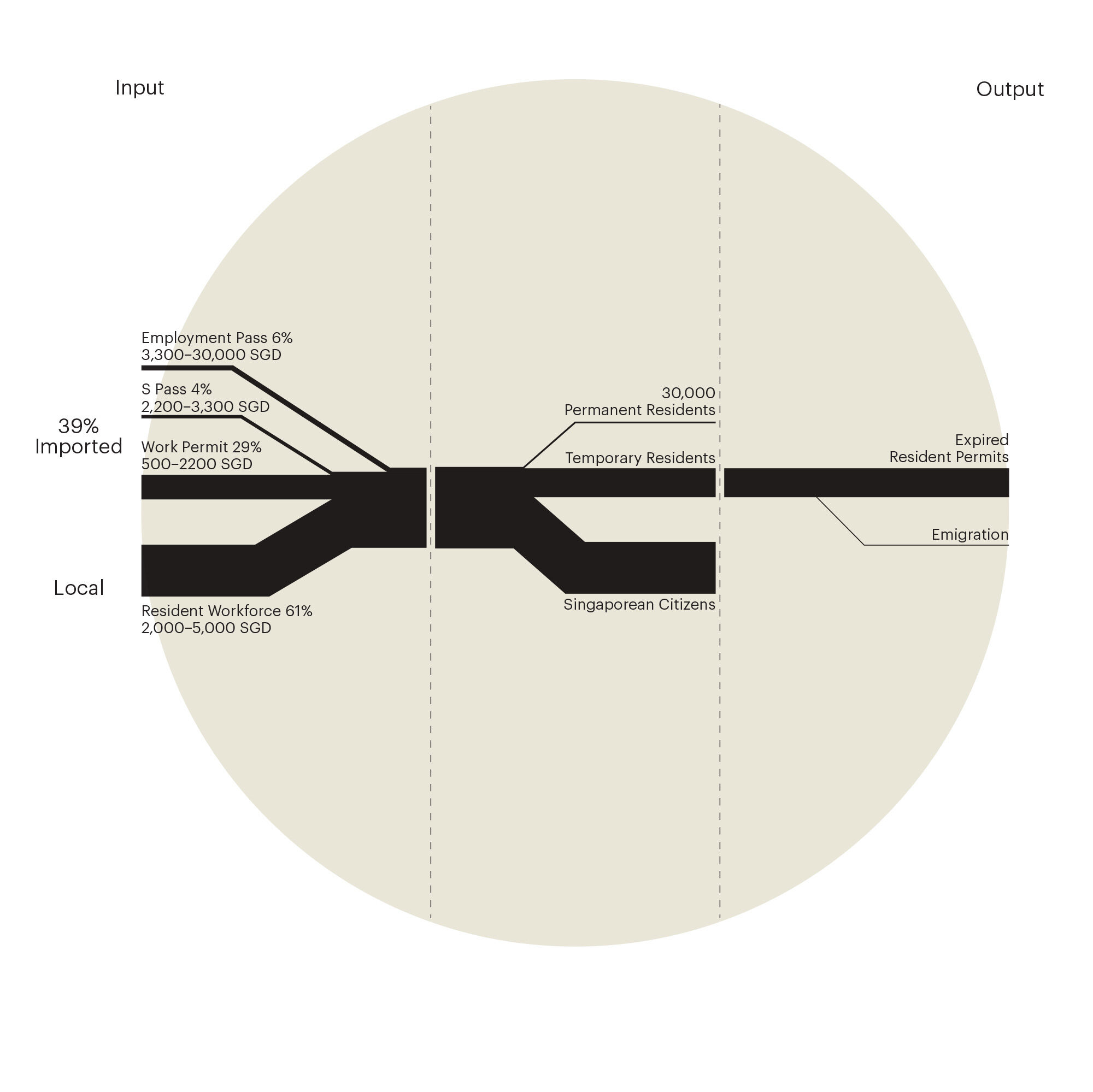

Singapore has traditionally been a place of labour immigration. In recent times, labour immigration has become a contentious socio-political issue due to the fact that Singapore’s population is ageing at an alarming rate, which increases the city-state’s dependency on foreign labour. The Singaporean Ministry of Manpower has established several categories of “non-resident workers,” which it defines largely based on income levels. Most notably, “work permit holders” are ‘basic-skilled’, S pass holders are ‘mid-level skilled’ and “employment pass holders” are ‘professionals, managers and executives’. Each of these categories defines specific administrative regimes and rights, which translate to different perspectives and conditions of life.

Hinterland

Metabolism

Extraction

Infrastructure

Organisation

Accumulation

Hinterland

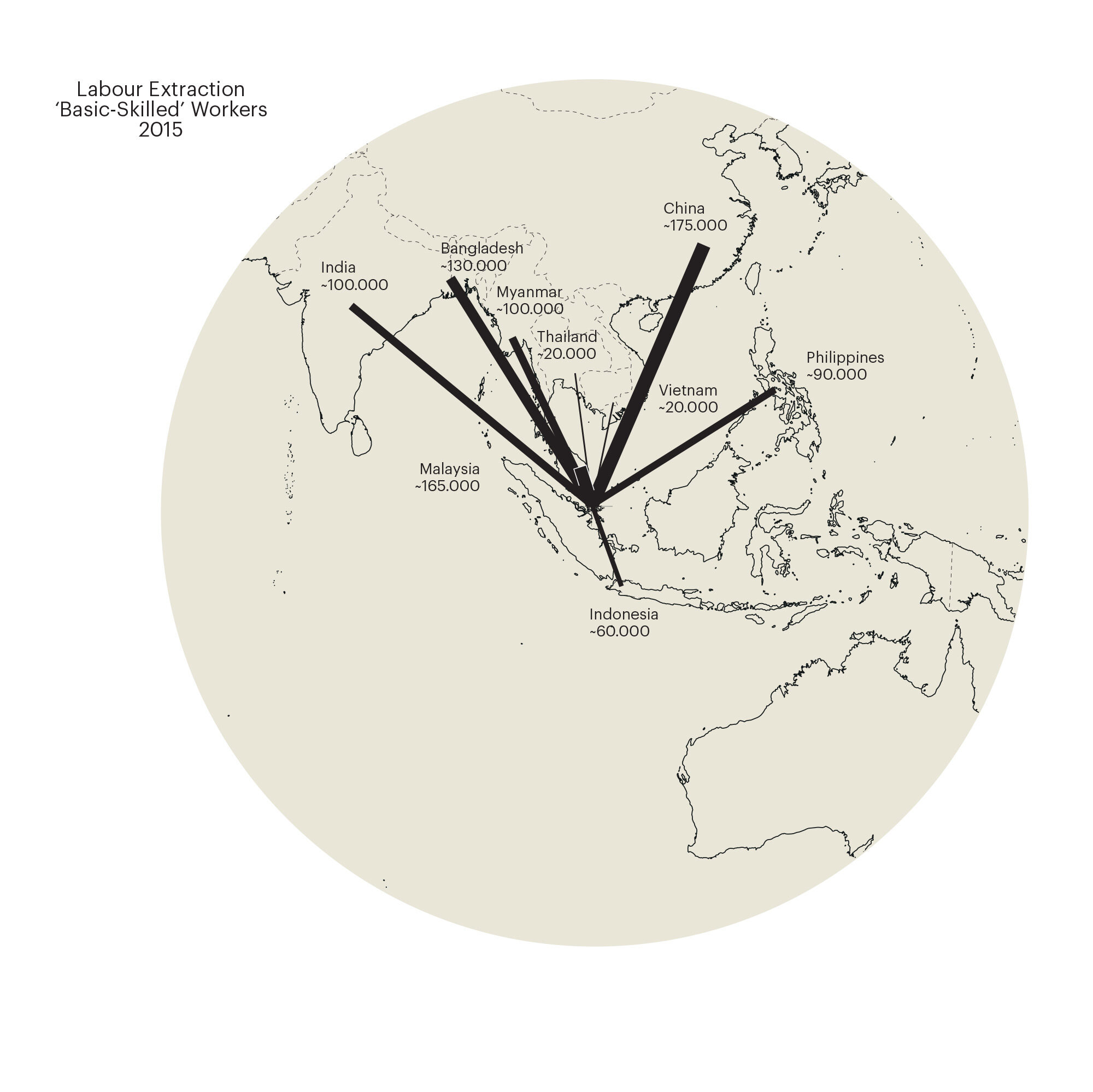

Singapore’s population is an assemblage of people that either came to the island to find work opportunities, or whose ancestors did so. At the time of independence in 1965, its inhabitants were mostly of Chinese, Malay and Indian origins. Last decades have seen Singapore shift its migrant labour politics as it began to welcome ‘basic-skilled’ migrant workers beyond its ‘traditional sources’—China, Malaysia and India— to include individuals from throughout Southeast Asia to take on employments in trades such as domestic help, nursing, construction work and bus driving.

Metabolism

Singapore’s latest regulations for migrant labourers make it impossible for “work permit holders” to become permanent residents in Singapore. These regulations make it clear that only ‘foreign talents’ (employment pass holders) can apply for permanent residency. Singapore can therefore only serve as a temporary working destination for every other type of migrant workers. As the number of these migrant workers increases drastically in relation to the resident population, Singapore is slowly evolving from an immigration-based country to a labour platform supplied by a transient workforce.

Extraction

Several criteria have influenced Singapore’s choices of preferential ‘source countries’ for its ‘basic-skilled’ workers. Notably, women (usually working as domestic helpers or cleaners) arrive mostly from Indonesia and the Philippines, while men (usually employed in construction or the marine industry) mostly come from India, Bangladesh and China. This general rule aims to limit the creation of new couples in Singapore, both inside foreign worker communities, and between foreigners and permanent residents.

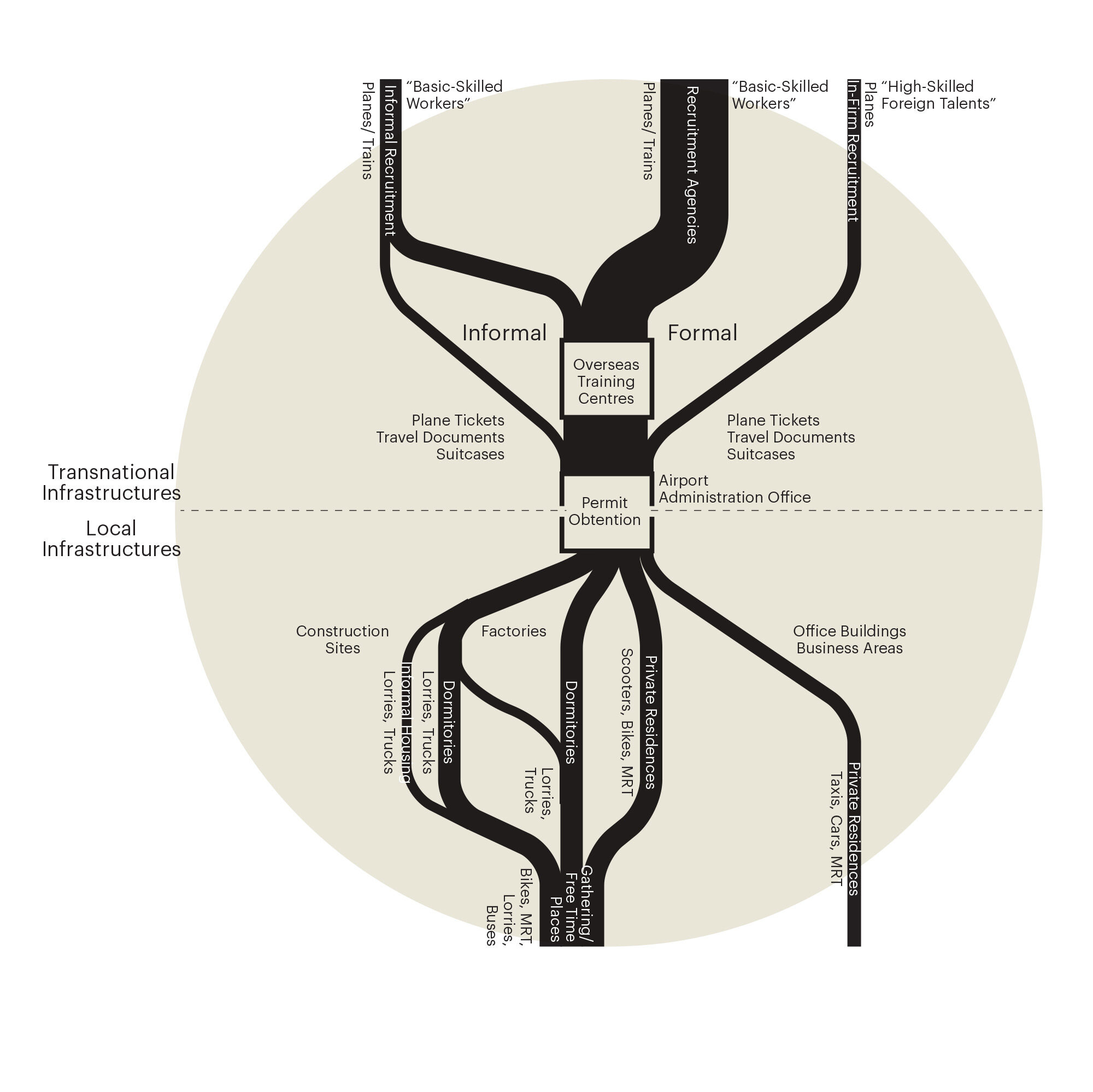

Infrastructure

The trajectory of each worker coming to Singapore is unique and usually a blend of formal and informal processes of recruitment. These processes usually amount to considerable debts for the migrant workers. Once in Singapore, the employers are legally obliged to provide them housing, usually in the form of dormitories or on-site quarters. The workers’ dependency towards their employers also includes meeting other everyday needs, such as transport, as they are not allowed to drive in Singapore.

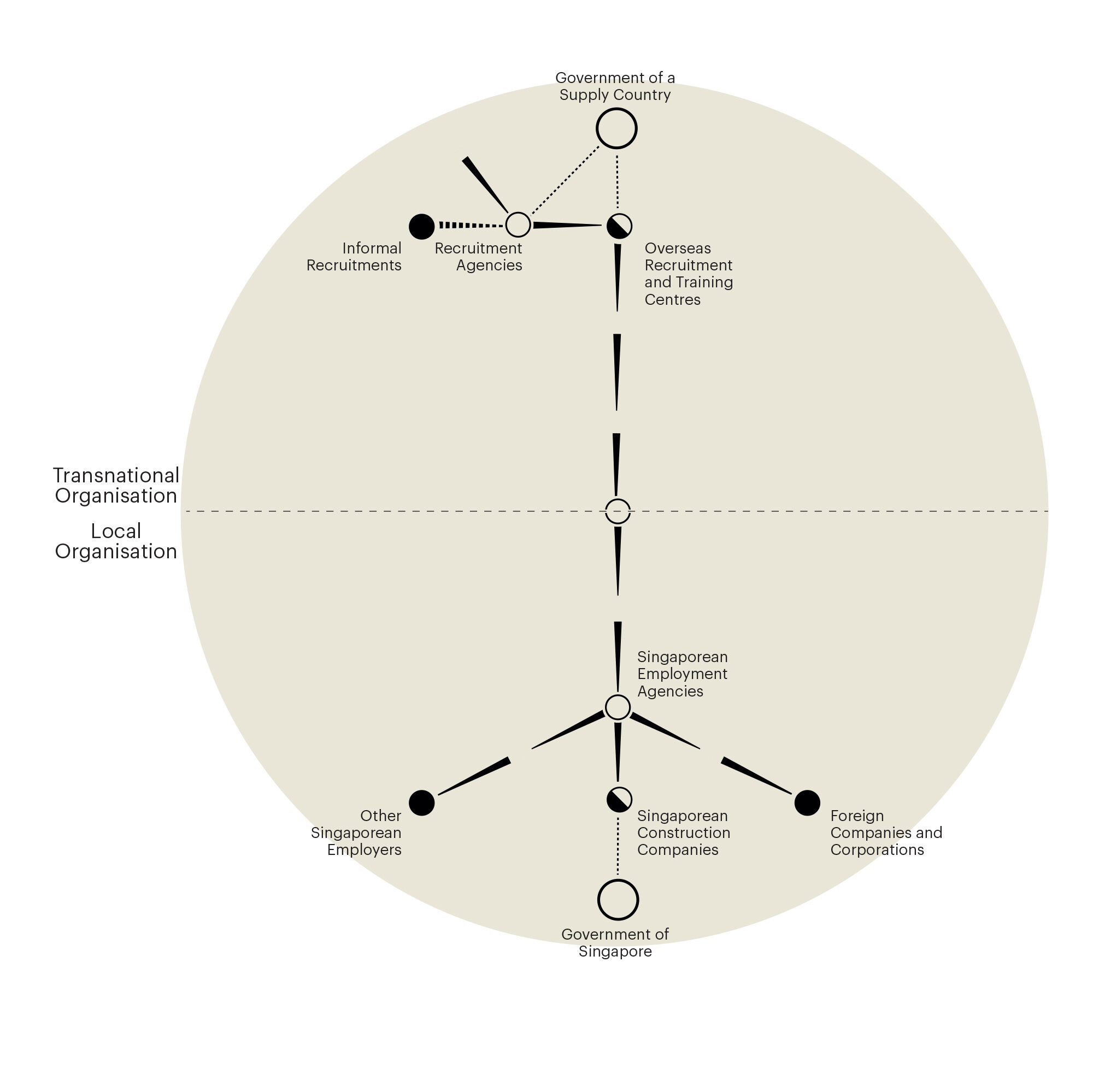

Organisation

In broad terms, the Singaporean private sector serves as a convenient mediator in the recruitment process between the state and potential foreign workforces. For certain sectors such as construction, Singapore has even opened “overseas training centres” in major cities throughout India, Bangladesh and China. These centres are owned and operated by private Singaporean construction companies and provide the necessary trainings and evaluations of workers defined by Singaporean governmental agencies. Therefore, they are a mean for Singapore to control the qualities of the labour force before it sets foot on national grounds.

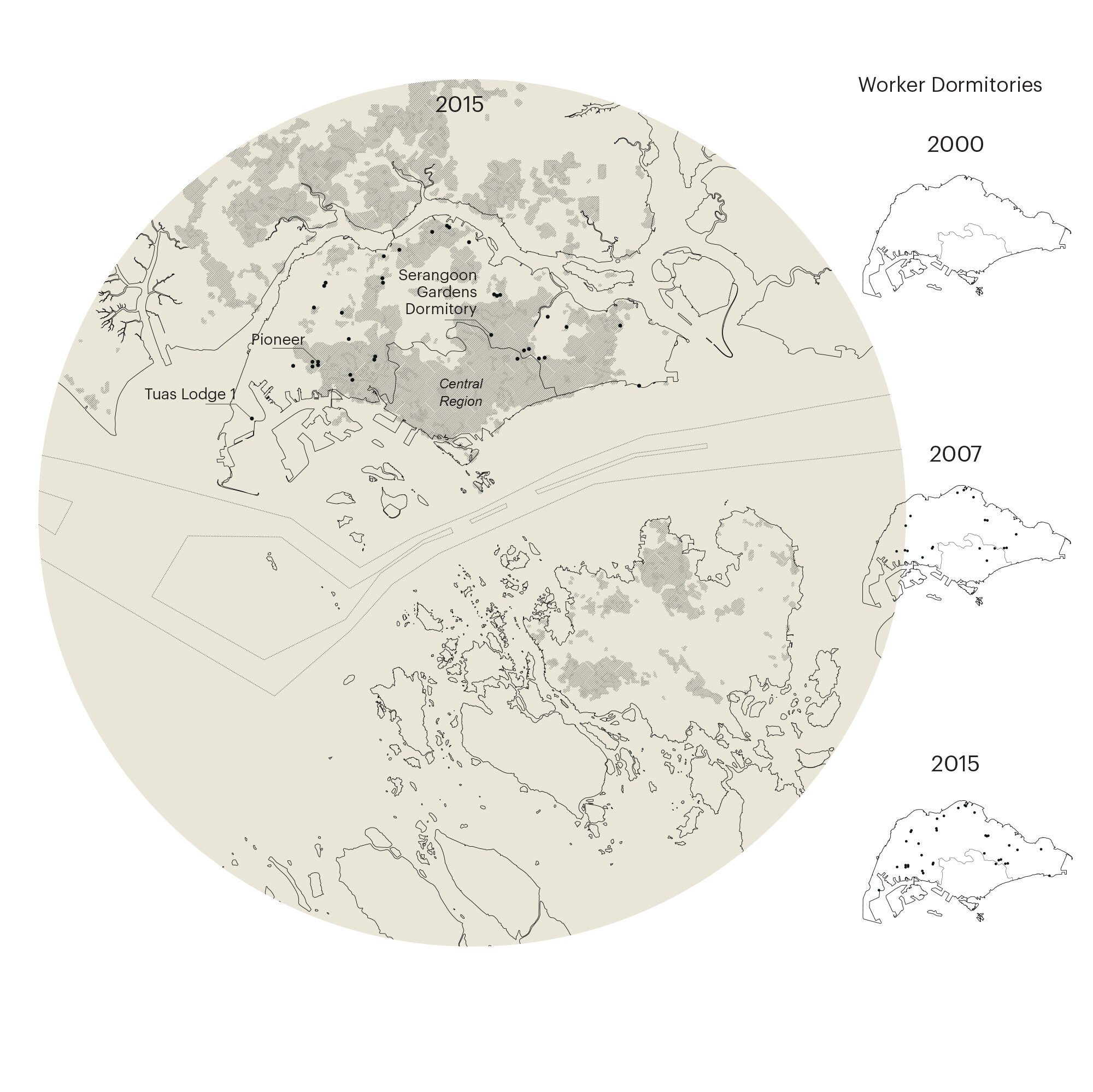

Accumulation

Poor housing conditions of foreign workers and the potential friction with residential areas of the city have been among the most sensitive topics in the last decade. The resulting urban strategy is somewhat paradoxical; migrant worker dormitories have been segregated from residential areas and dispersed to non-residential zoning areas. Migrant worker dormitories are in fact commonly located in industrial zones, “reserve sites” (plots kept vacant for further planning), or “special uses” (military functions, reservoirs, cemeteries,…). Most dormitories are either contained within such non-residential land-use areas, or located at the threshold between them and residential zoning areas.

Although Singapore has no natural oil reserves of its own, the oil trade has been essential to its economy since the 1890s. Today, Singapore is a crucial nexus within the global oil economy. Crude oil and petroleum products account for the largest shares of all imports and exports in Singapore. While their role in electricity production has greatly diminished, the construction of Jurong Island facilities beginning in the 1990s has triggered an ongoing boom in Singapore’s oil related industries.

Hinterland

Metabolism

Extraction

Infrastructure

Organisation

Accumulation

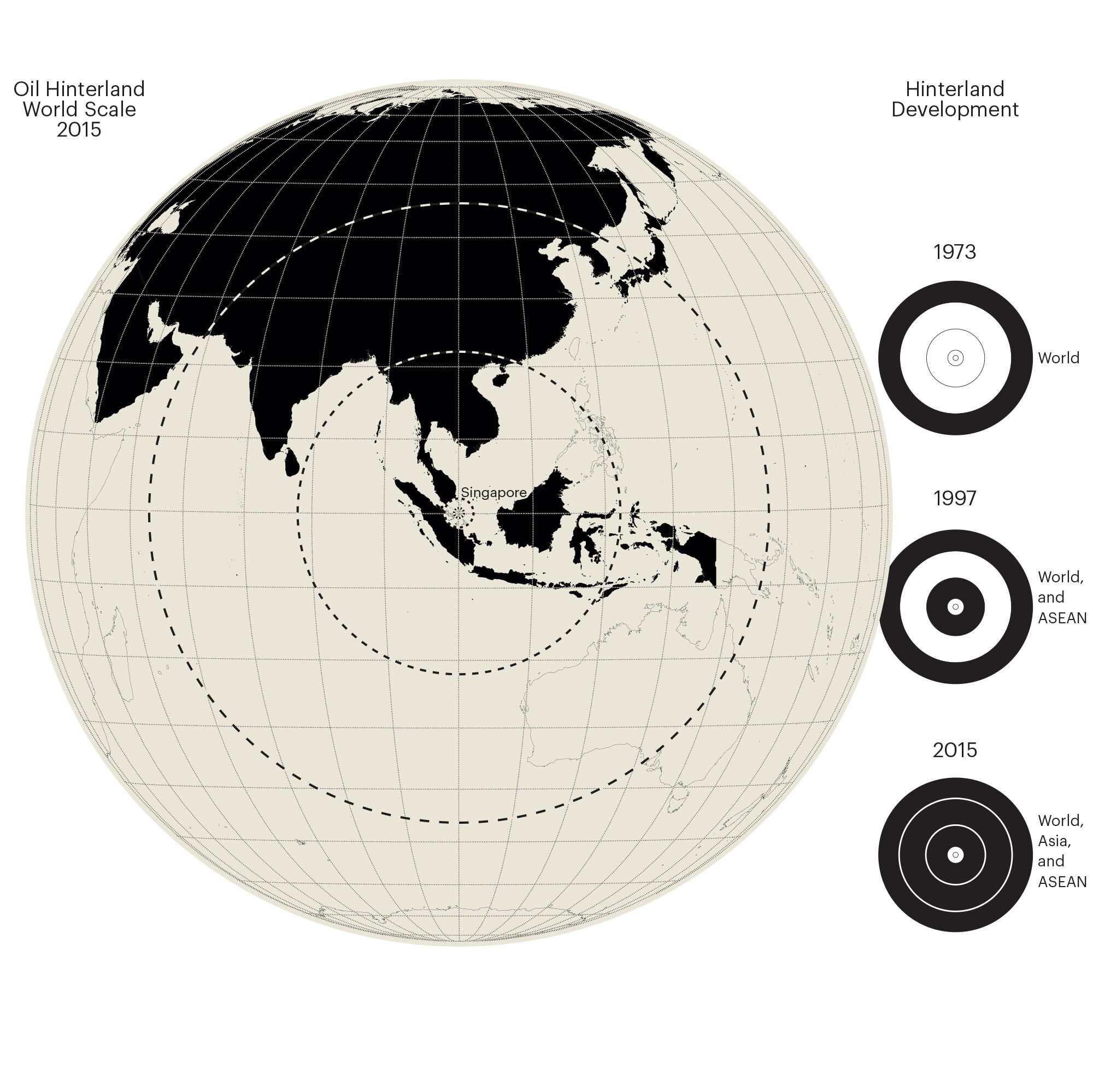

Hinterland

As both the oil trade and its refining processes have become more complex, Singapore’s oil hinterland has increasingly diversified as it began to trade in a wider range of oil products, from more countries than it had in the past.” For example, in 2014, Singaporean imports of crude oil and refined petroleum products from Malaysia surprisingly equalled those from Saudi Arabia. In addition, Singapore’s reputation as a business location has become a more important factor for its leading role in the oil industry than the actual presence of oil resources.

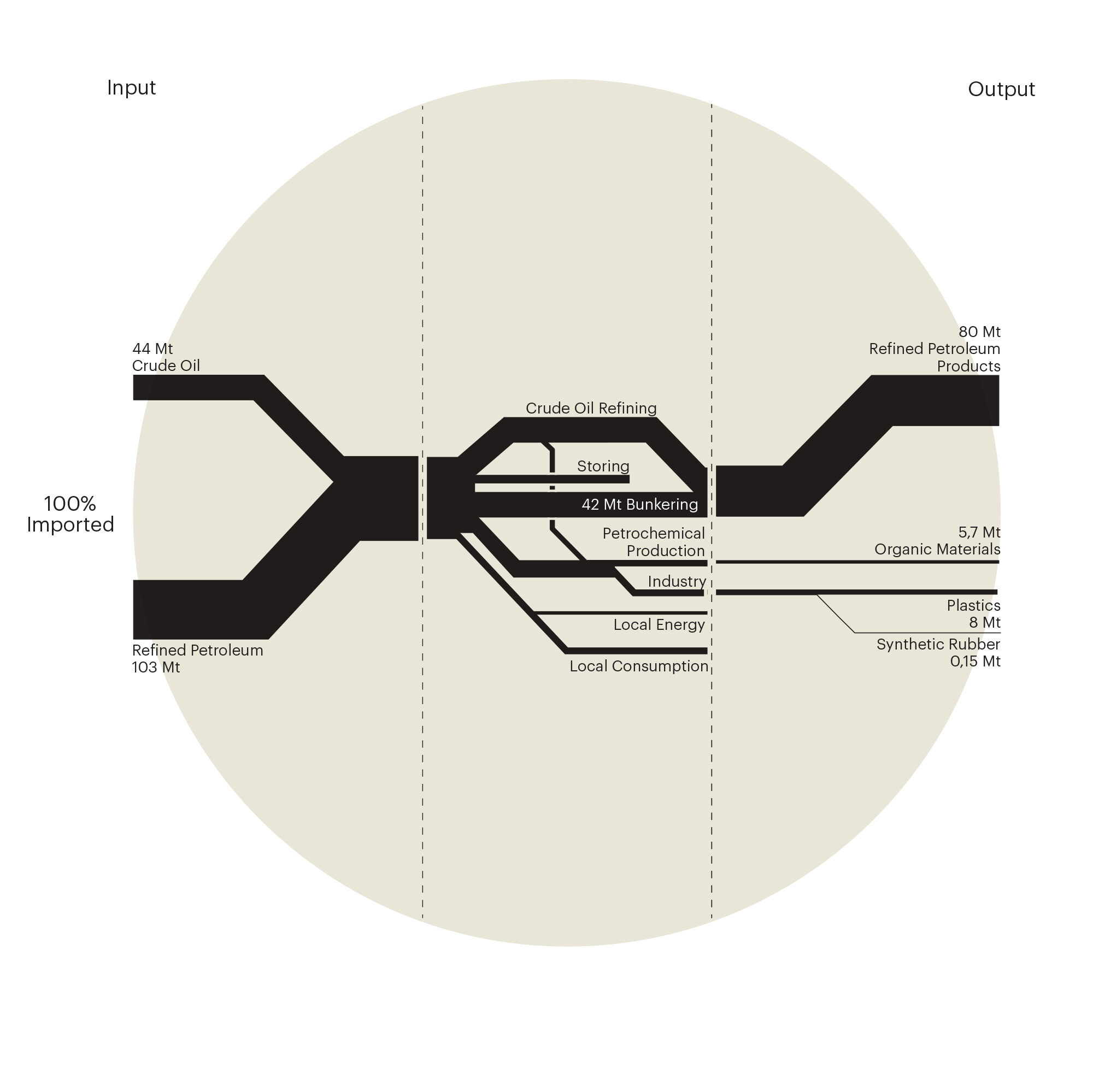

Metabolism

While local demand for oil in Singapore is negligible, the storage and trade of oil constitute a crucial engine for the national economy. Singapore has become a global centre for both oil refining and the petrochemical industry. Although the share of crude oil in Singapore’s total oil imports has steadily declined, the city-state remains an important refiner in Asia. At the same time, the Port of Singapore continues to rely on a ceaseless supply of bunker fuel for incoming ships.

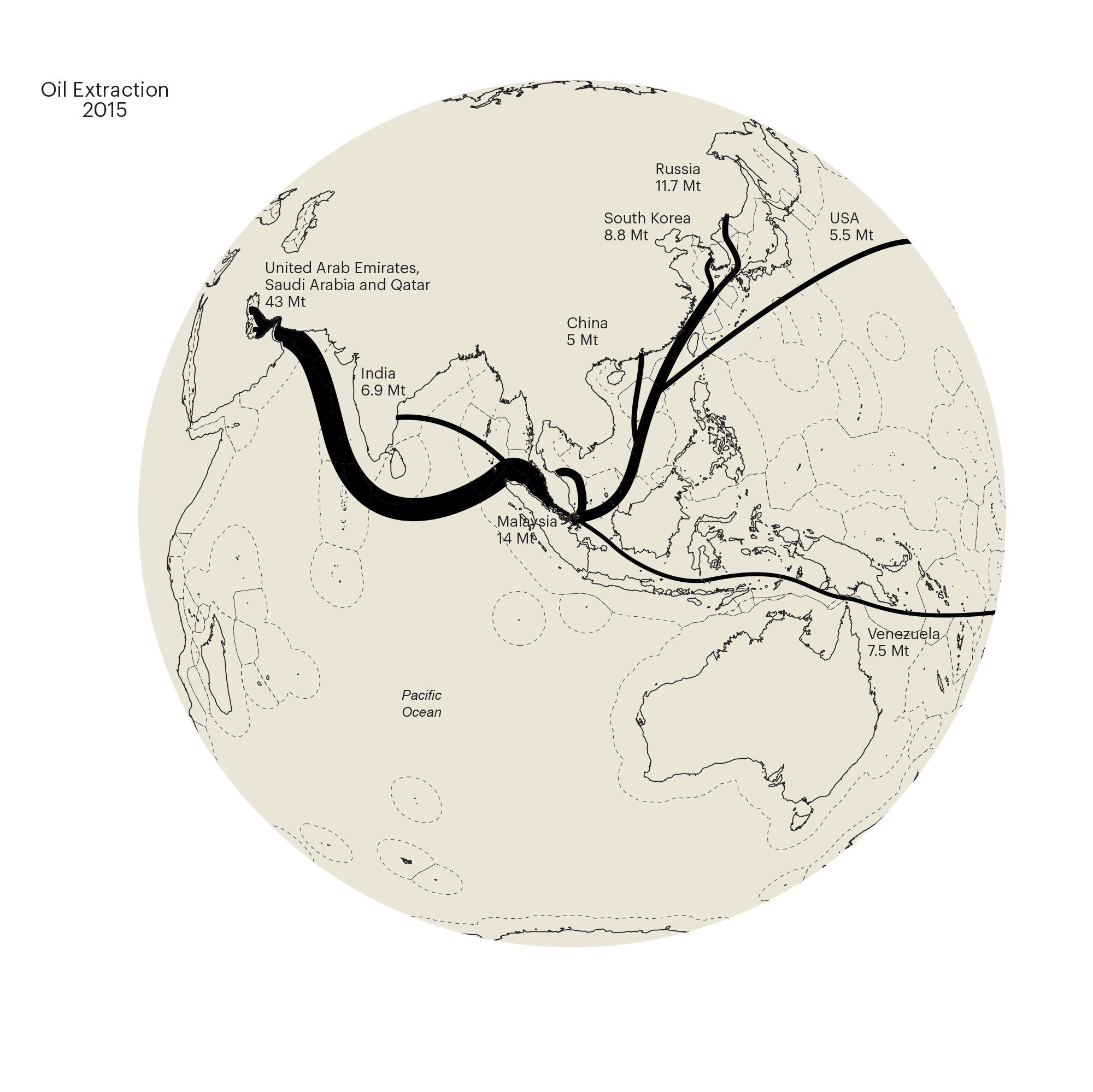

Extraction

All oils and petroleum products arrive to Singapore by oil tankers, some of which transport over 500,000 metric tons at a time. As 27% of the annual global oil trade passes trough the Strait of Malacca, Singapore benefits from its geostrategic location between petrol-producing countries in the Middle East and oil markets in Far East Asia. As more countries in the region, including Malaysia and Indonesia, have expanded their oil refining capacities, they have helped Singapore diversify its import sources away from its traditional trade links in the Middle East.

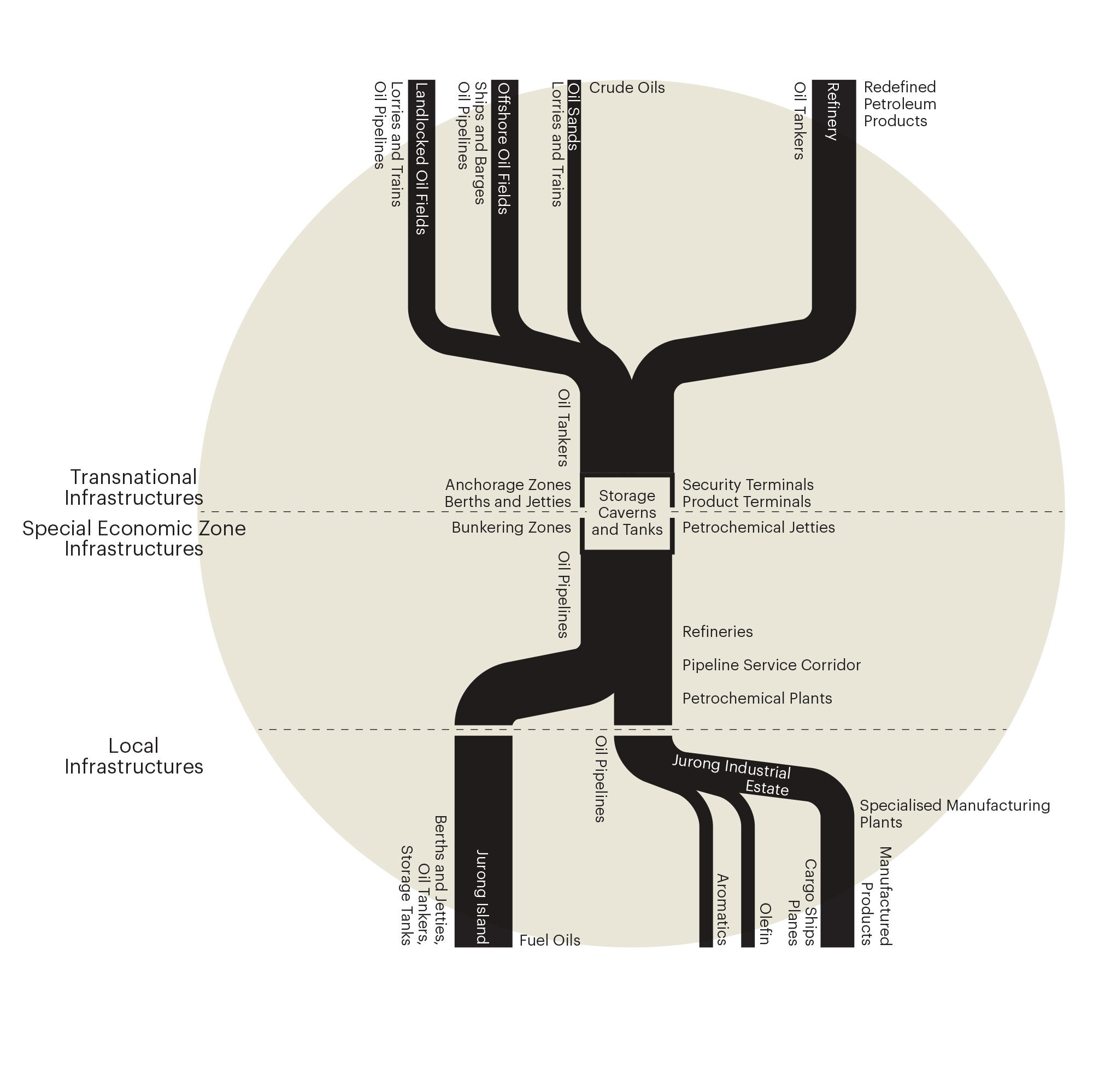

Infrastructure

A complex network of infrastructures both technical and social-political shape the conditions of the oil trade. Oil storage, processing and trade take place under special economic conditions of tax breaks and other exemptions facilitated by the government. To support the growth of a petrochemical cluster and various related industries, Singapore financed the construction of Jurong Island and its elaborate facilities, and maintains a stringently regulated and secured environment for companies that operate there.

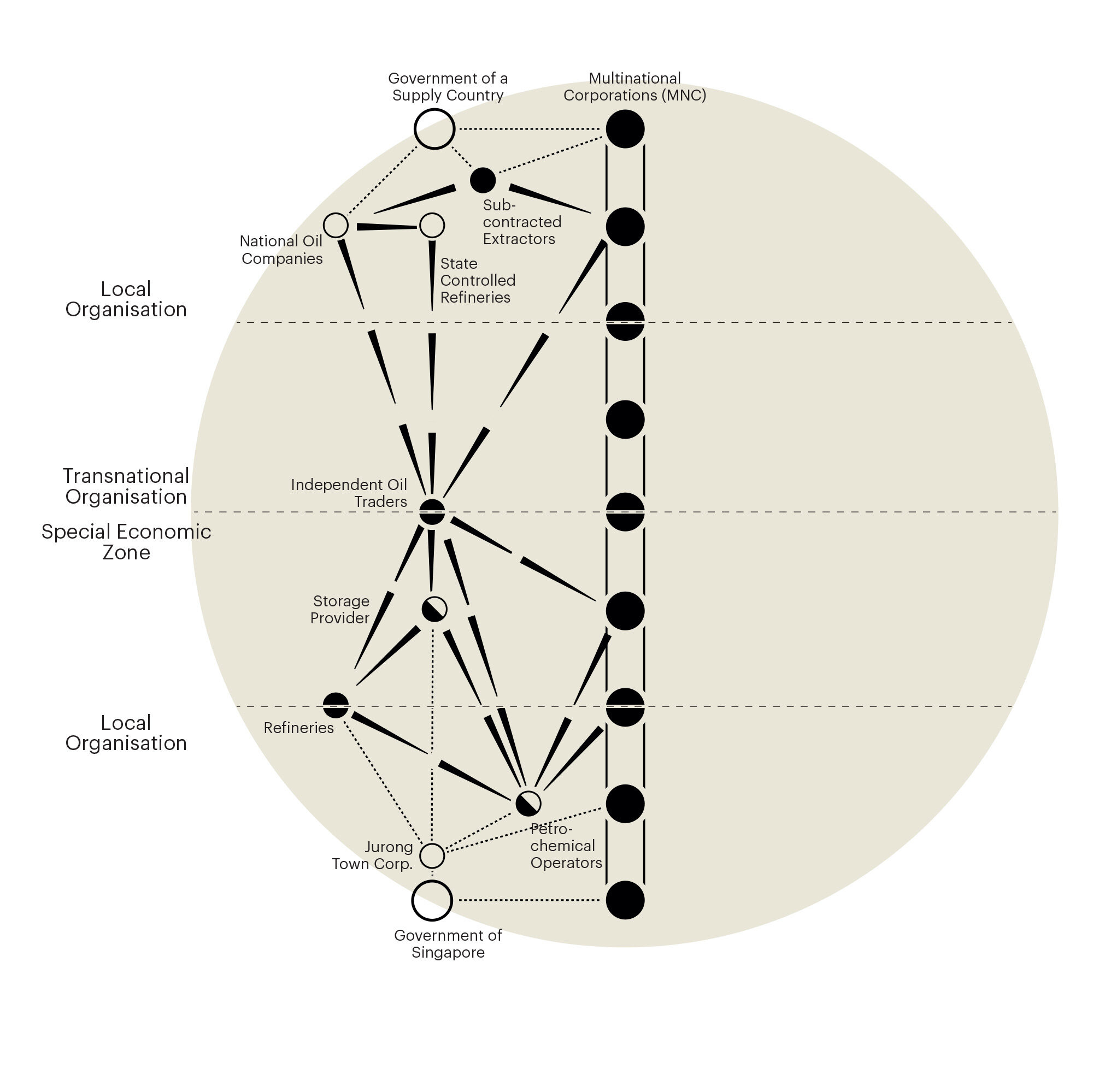

Organisation

The industry is essentially controlled by the six oil majors (Royal Dutch Shell, Exxon Mobil, BP, Total, Chevron and Eni) that have been exploiting and trading oil for over a century alongside national oil companies. Singapore’s success as an oil hub is attributed to the government’s hands-off policy towards the industry and its multinational corporations. However, the Singaporean government provides incentives to support the growing cluster of oil related industries, from chemical manufacturing to ship maintenance, benefitting from the CBD.

Accumulation

Singapore’s expansion as a major centre in the global oil economy has begun to spill over its borders into the neighbouring territories of Malaysia and Indonesia. Singapore’s development in keeping up with industry demands has included the deployment of land reclamation strategies, underground excavation and ceaseless infrastructural refinement, accompanied by rising land, labour and material costs. At the same time, new oil facilities and urban and population growth related to these industries have spread in the trinational region spanning Singapore, Johor and Riau Archipelago.

Singapore’s relationship with its immediate, geographical hinterland is manifest in the cross border region popularly known as SIJORI (for Singapore-Johor-Riau Archipelago), now counting more than eight million legal residents and an unspecified migrant population. In the late 1980s, SIJORI emerged as a political construct among Singaporean, Malaysian and Indonesian governments to acknowledge the process in which Singapore’s economy had begun to expand over its borders. Today, despite the high degree of synchronization among economic activities in the region, the political articulations of common interests still remain scarce.

“Cross-Border Metropolitan Region Singapore, Johor, Riau Archipelago” describes the region’s urban potentials in terms of six characteristic “Territories of Urbanisation”: 1.Trinational Metropolis (urban centres and residential fabric served by social and technical infrastructures); 2.Cross-Border Territories (urbanisation produced through international investment); 3. Strategic Reserved Land (reserves for future urban expansion, military and water storage); 4. Industrial Primary Production (principal functions include palm oil industry in Johor and mining in Riau Archipelago); 5.Urban Sea and Air (areas in the function of shipping, petrochemical industries and air transport); and 6—Quiet Archipelago (shrinking rural areas).

Looking at Singapore’s proximate territories in the Malaysian state of Johor, and the Indonesian Riau Archipelago, the research does not present the common view of Singapore as a geographical and metaphorical island, developed according to the paradigm of a global city-state, but articulates a counter paradigm that posits Singapore as an open and connected cross-border metropolis. In this view, Singapore is represented as a city whose present and future are tightly linked to its neighbouring region.